An Exclusive Interview with Fashion’s OG Bad Boy, the Mysterious Manfred Thierry Mugler

Manfred Thierry Mugler is tap dancing for me. It’s maybe the last thing I expected from the famously reclusive designer. But apparently it doesn’t take much to get Mugler dancing. “Your shoes are so cute!” he says, while doing an impromptu buffalo-step shuffle. “Very Fred Astaire.”

I look down at my two-toned spectator-ish flats and then back at Mugler, who is still moving with such casual grace that it seems unfair. He looks as if he could have eaten Fred Astaire, like he’d stepped out of a George Quaintance print so he could put on some leather in time to be in a Tom of Finland illustration.

But his lightness and rhythm shouldn’t be surprising: Long before he became a celebrated designer, perfumer, photographer and artistic director, Mugler was a ballet dancer, and after he left fashion in 2002, he transformed his physique. “The physical mutation was a sort of return to myself—a repairing and reconstruction, too,” he once said.

“The physical mutation was a sort of return to myself—a repairing and reconstruction, too.”

We take our seats at the conference table at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA) to chat about the Thierry Mugler: Couturissime exhibit that will open on March 2. It’s the first exhibition of his work and a considerable coup for the museum. Mugler has led a rather hermitic life for more than 15 years, since Clarins—which owned his clothing line—shuttered the business. This marked the end of a spectacular career that was launched in 1974 in Paris and reached its zenith in the ’80s and ’90s. But once Mugler was out, he distanced himself from the industry—and who the industry had made him into. He started referring to himself as Manfred (his first name), and he bulked up.

It left him practically unrecognizable, which was the intent, says Thierry-Maxime Loriot, the exhibit’s curator. “He told me that after he left the fashion industry, it annoyed him when people recognized him. He felt ‘Thierry Mugler’ was a label, a brand. He wanted to move on to other things.” However, Mugler still continued to work with Clarins on fragrances. In addition to the iconic Angel, which was released in 1992, he created Alien in 2005, Womanity in 2010 and Aura in 2017. Today, these scents—and the flankers that followed—continue to generate close to $757 million in annual sales.

Given his sensitivity about reliving his past, I ask Mugler how Loriot had seduced him into agreeing to the exhibit. “Oh, that’s a funky question,” he laughs, explaining that he appreciated they wanted to do a “creation rather than a retrospective.” At this point, Loriot, who also curated Jean Paul Gaultier: From the Sidewalk to the Catwalk and produced Viktor & Rolf: Fashion Artists, interjects that Mugler isn’t a nostalgic person. “He doesn’t look at his old work and say ‘These are my babies.’ Instead, he asks ‘How can we transform them?’”

During the two and a half years that it took to create the exhibit, the pair worked closely to choose more than 140 outfits that Mugler designed between 1973 and 2001. In addition, there are 100 photos of his designs, captured by Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton and Herb Ritts, as well as videos, sketches and costumes from his stage productions.

“He has always been an outlier whose work is provocative and unapologetically designed for women who own their sexuality and power.”

Loriot says the exhibit will be immersive, with animated holograms, infinity rooms and a wild forest created by Rodeo FX, the same company that created special effects for Game of Thrones and Birdman. “The main message behind the Mugler exhibit is to not fear your desires,” says Loriot. “His work is a timely example of what we’ve lost in the fashion world and what we’re beginning to crave again.”

Looking back at Mugler’s shows on YouTube, I can see that the designs were visionary, yet their fantastical, futuristic and sensual aesthetic seems out of step with fashion’s preoccupation with being real, relevant and representative. He was the first (pre-Alexander McQueen and pre-Marc Jacobs) to produce astonishingly theatrical runway shows. His advertising campaigns, which he often shot himself in exotic locales, fuelled pre-online #fomo envy.

His clients? Basically a stylish A-list gaggle that included David Bowie, Jerry Hall, Diana Ross, Ivana Trump, Celine Dion and all the iconic supermodels, not to mention Beyoncé and Lady Gaga. He has always been an outlier whose work is provocative and unapologetically designed for women who own their sexuality and power. It’s also for women—and audiences—who share his mischievous sense of humour.

Holly Brubach, who covered fashion for The New Yorker and The New York Times Magazine during Mugler’s epoch, suggests that his work might be viewed with a different lens if it were being released today. “I think there might be a backlash about the way it presents women,” she tells me later, over the phone. “I suspect that the humour we saw at the time wouldn’t be there today. I think the striking thing about Mugler’s work is that the women who wore it owned it. It wasn’t something that had been imposed or foisted on them by some man and they were trying to look attractive based on his terms.”

“I think the striking thing about Mugler’s work is that the women who wore it owned it. It wasn’t something that had been imposed or foisted on them by some man and they were trying to look attractive based on his terms.”

Brubach interviewed Mugler for The New York Times in 1994, when she set up a Q&A between him and Linda Nochlin, a noted feminist art historian and critic. She thought they would be unlikely conversation mates because, at the time, some of Mugler’s designs could have been interpreted as sexist to an almost cartoonish degree.

To her surprise, however, they really hit it off. Nochlin felt that Mugler’s fashion empowered women to appropriate their own sexuality: “It’s so extreme that these women aren’t sex objects; they’re sex subjects,” she said.

But the designer also played with the notion of femininity. “Mugler was at the far end of the spectrum in fashion that was just on this side of drag,” explains Brubach. “One of the things that interest me about drag is what it says about women and what constitutes femininity—in terms of both appearance and behaviour. I think Mugler did the same thing, but he was doing it for women. It was a time when women were inventing themselves in unprecedented roles, and a big part of that was their appearance and trying to find a new way to be in the world.”

“It was a time when women were inventing themselves in unprecedented roles, and a big part of that was their appearance and trying to find a new way to be in the world.”

Eric Wilson shares Brubach’s fondness for Mugler’s work. His first (and only) encounter with Mugler took place in 2010, when he wrote a profile on the designer for The New York Times to coincide with the launch of Womanity. “I grew up in the ’70s and ’80s, and he was one of the first names in fashion that I connected with,” recalls Wilson, who is now the fashion news director for InStyle.

“To see his work through the lens of contemporary society will be fascinating. These pieces did cause controversy in their time, but I predict people will react positively to these clothes because they are so different from anything you see in the world. There’s this embrace of the superhero mystique, which is really important in his work as it’s about fantasy and assuming different identities. It’s like a warrior putting on a battle suit.”

“When I look at his pieces, it’s really clear to me that the intent wasn’t at all about misogyny but, rather, empowerment. His designs were progressive, and his vision was remarkable.”

Wilson adds that Mugler’s work references comic books and adventure series that were created by populations in America that had been oppressed, such as Jewish people and gay men. “It was really about breaking out of the boundaries that are imposed on us and that we impose on ourselves,” he says. “When I look at his pieces, it’s really clear to me that the intent wasn’t at all about misogyny but, rather, empowerment. His designs were progressive, and his vision was remarkable.”

And how does Mugler think a younger generation will react to his chrome-corseted robot women and vampy femme fatales encased in vinyl and rubber? “I hope they will look at the quality,” he says. “I think beauty is the human emotional vehicle between us and it’s very important. It’s important in architecture and painting and art, but people don’t invest in beauty anymore. They invest in violence, and that’s why I tell people to look beyond the sexual aggressivity that’s sometimes in my clothes: Don’t look at the cliché; look at the way it was done. There was always this balance to make it beautiful, high-class and respectful for the human being.”

“[Beauty is] important in architecture and painting and art, but people don’t invest in beauty anymore. They invest in violence, and that’s why I tell people to look beyond the sexual aggressivity that’s sometimes in my clothes.”

I’m not entirely sure what Mugler means, but I suspect he’s urging us—as he always has with his work—to think beyond what is predictable. While he likely came into the world imprinted to be an iconoclast, Mugler says he was fortunate to have met exceptional people who pushed him forward—from the person who helped him get past his hippie life, living on a houseboat in Amsterdam, to the person who helped him come down from his mushroom-laden life in Kerala, India.

Later, it was the coach who transformed his physique and the body therapist who understood that pain is a necessary part of growth. Most importantly, four years ago, he also met the man he calls the love of his life. “He’s the most free, real, simple and beautiful person I have ever met,” says Mugler. “I do have a lucky star on me.”

That star has been a recurring motif in Mugler’s work—both in his designs and even in the shape of the iconic Angel fragrance bottle. On his right hand, he wears a macaron-size golden star ring that he describes as his armour. His fascination with stars began when he was a boy.

He’d often run away from home and spend the night on a bench staring up at the sky. He always looked for one blue star, which he felt was a harbinger of better times. The night sky continued to comfort Mugler when he estranged himself from his parents at 14 to join the ballet in his hometown of Strasbourg, France.

A writer once suggested that his adolescent discontent stemmed from his feeling conflicted about his sexuality, but Mugler scoffs at that suggestion. “I didn’t have a problem with my sexuality or identity,” he says. “I had a problem with my family, and I had a problem with the world. I was feeling out of place, and I was feeling very miserable. I was in the ballet for six years, and no one in my family came to see me onstage; I was the ugly duckling who left the theatre alone. I guess I was too bizarre. I would watch the skies at night and look for the blue star and know that I had to hold on.”

“I didn’t have a problem with my sexuality or identity. I had a problem with my family, and I had a problem with the world. I was feeling out of place, and I was feeling very miserable.”

It’s a beautiful, sad, poignant memory. If I didn’t know better, I’d almost call it nostalgic. Of course, stars aren’t Mugler’s only inspiration. Animals—and the symbolism behind them—find their way into his work, including the mythical phoenix and the boar. The first is a fitting metaphor for a man who has undergone his own dramatic metamorphosis—in terms of both his career and his body.

But what about the boar? A Google search reveals that this creature symbolizes freedom. “‘Boars have few predators, so they have the luxury of living freer than most creatures,’” I read out to Mugler. “‘They do what they want, when they want.’ That pretty much sums you up, doesn’t it?” He laughs, sits back in his chair and says: “I love that. I’ll go for that.”

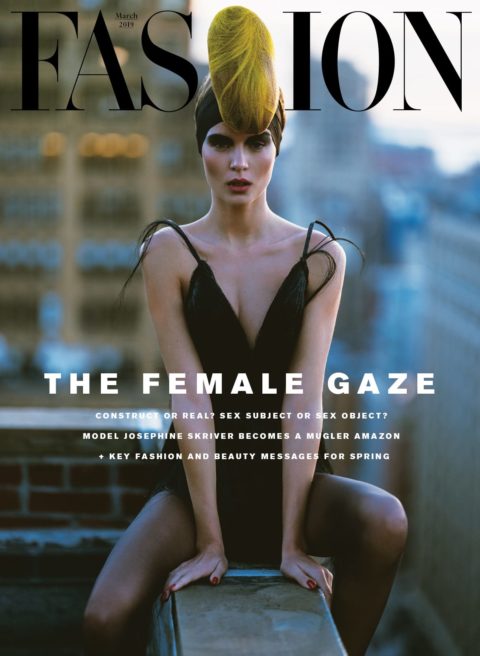

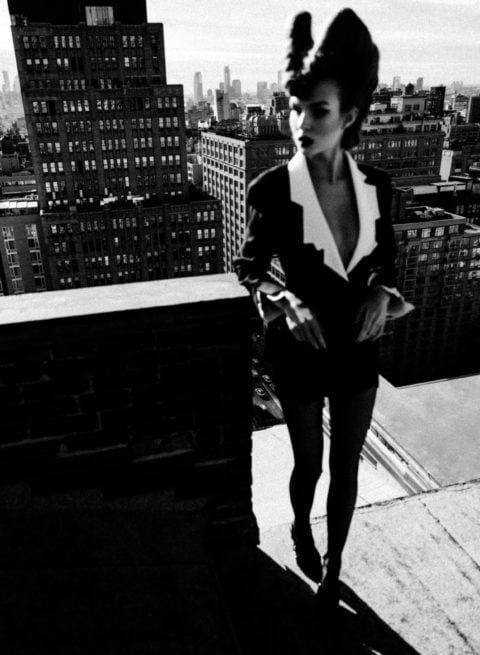

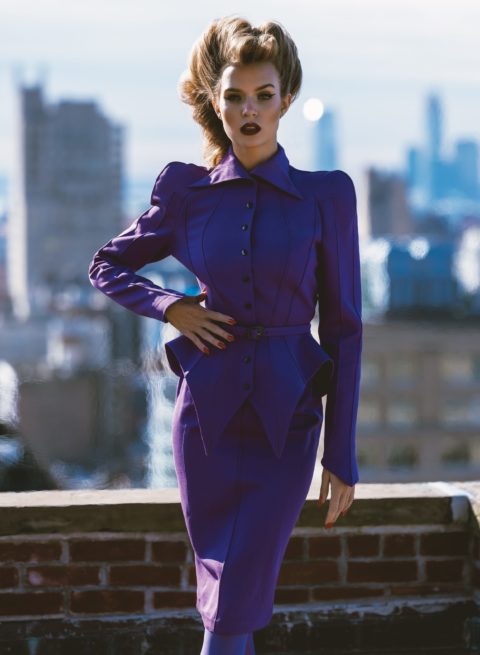

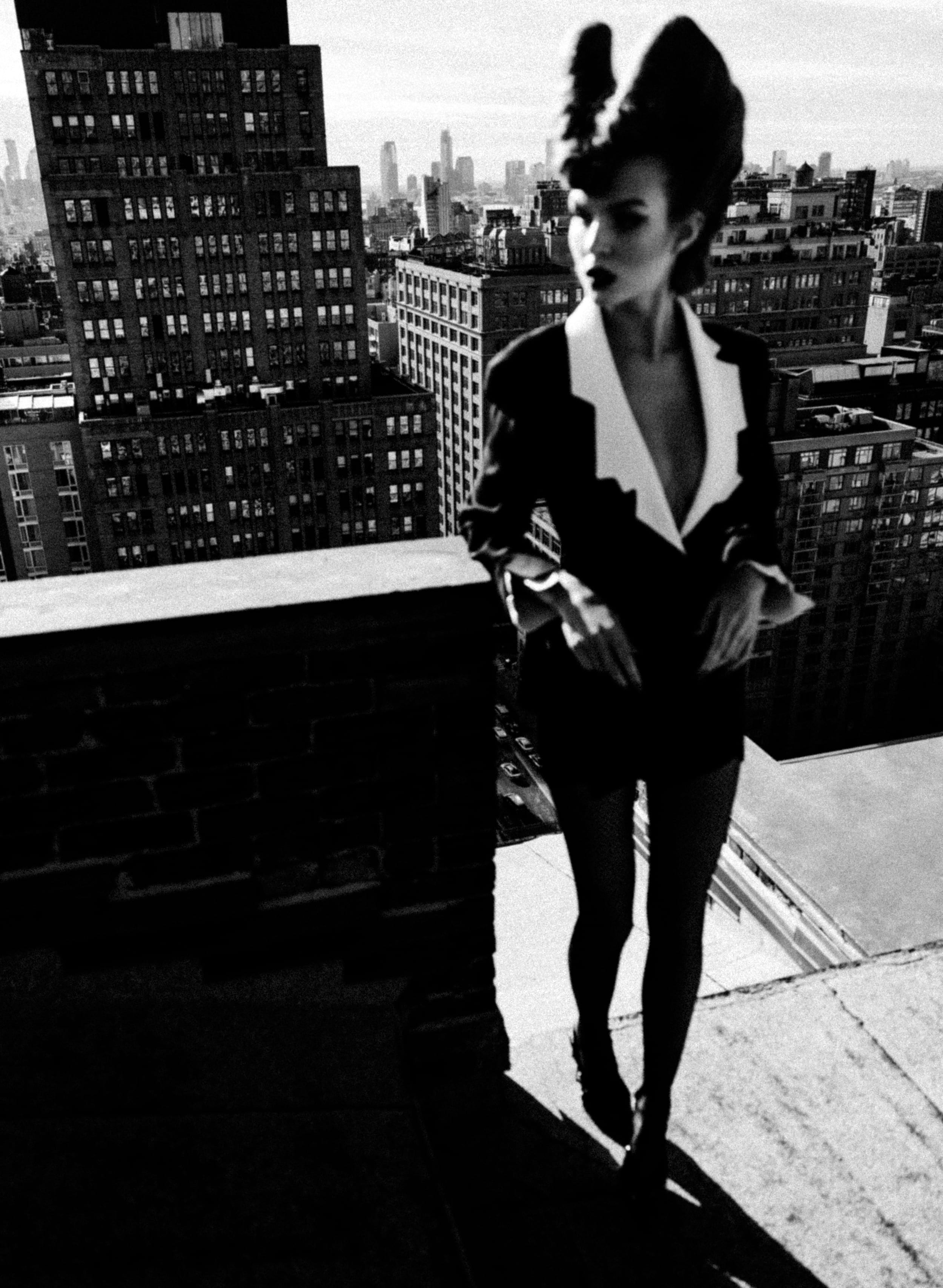

See every look we pulled from the Thierry Mugler archives as modelled by Josephine Skriver below and in our March 2019 issue, available now.

The post An Exclusive Interview with Fashion’s OG Bad Boy, the Mysterious Manfred Thierry Mugler appeared first on FASHION Magazine.