Architect Philip Beesley on his Friendship with Iris van Herpen

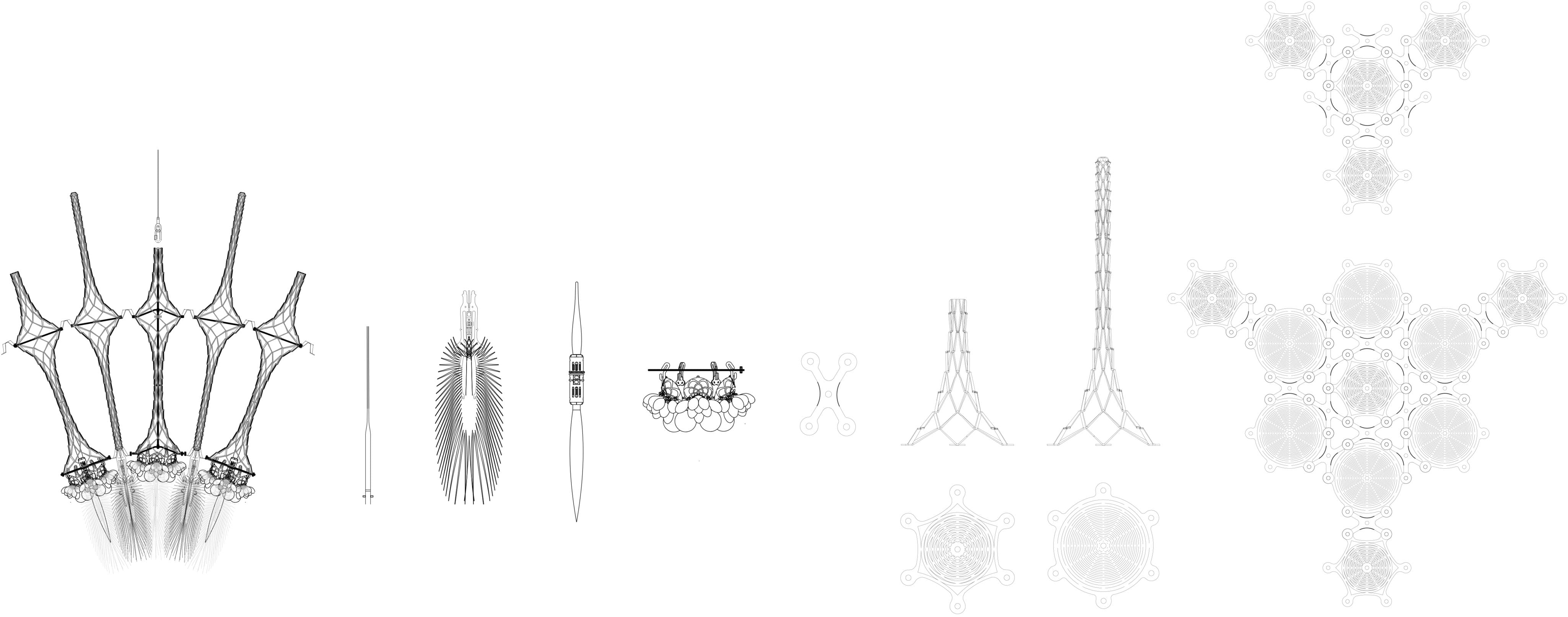

If you haven’t heard of Philip Beesley before, here’s a crash course. He’s a 61-year-old Canadian architect and professor at the University of Waterloo, whose body of work involves the creation of transgressive, sentient structures — which is just as weird as it sounds. He also happens to be one of Iris Van Herpen’s closest friends. This Sunday, Beesley’s immersive installation, Transforming Space, opens in concert with Iris Van Herpen: Transforming Fashion at the Royal Ontario Museum.

We caught up with the visionary architect to discuss his deep friendship with Iris, their longstanding collaboration, and mutual desire to create a body of work that thrives on the edges of scientific possibility.

FASHION: How would you describe Iris’ work?

Philip Beesley: I would say that it is defined by curiosity, wonder, and absolute command of craft, plus direct, precise, factual grounding. Those two things together make for the most delicious interchange.

What initially appealed to you about collaborating with Iris?

I was very, very attracted, when I first thought about collaborating with Iris, to the technical precision and the sheer wealth of experiment found in her body of work. What I didn’t realize, is what an extraordinary wonderful person she was. When we were together in person, in those first conversations, we sat together and what we intended to be just half an hour turned into a long afternoon and evening where the conversation just kept spinning and spinning. We talked about how to make things. We talked about potential collaboration. But we also talked about our memories and our hopes and the way our bodies feel. It became a very lovely, playful friendship in a very short time.

How were you introduced?

I met Iris for the very first time when I discovered that she had credited a whole collection to my work. Then quickly after that in 2012, we entered into correspondence and arranged to meet, and then the conversations just started accelerating.

What drives you to keep collaborating?

I think that we have become deep friends. We’ve also become deeply connected professionals, in the sense we are working on a body of research and trying to learn how to make new fabrics with iridescence, stretch material, and material that’s on the very brink of coherence. We try to make things that are reactive, deeply sensitive, trembling, oscillating, shimmering. Those kind of qualities are precarious, and they require new design techniques. They require a constant innovation of finding out ways of working, as well as established vocabularies and sources. So that deeply interwoven practice makes for constant conversation.

What inspires you to continuously explore this vanguard of technology?

When I think about what continually inspires me to keep at an edge like this, I think we are discovering that something matters. That instead of needing to accept the world as it is and inherit it, you can actually make a contribution by working right at the edge where we discover things. We have a standing joke between us: if I give her a fabric, she’ll usually turn it inside out. It produces something quite extraordinary, just that moment of surprise and looking at how we can transform and discover and continually find something new that is fresh.

How does the collaboration function?

The question of just how such collaboration between different worlds, different crafts would actually work is a very interesting one. We’re across the Atlantic. I work in very large, strong structures, and she works in intimacy. Yet those two worlds are quite close together in that we can readily have a conversation online. We can offer each other a piece of fabric or a sketch and immediately start working. So what happens is, I or Iris might have a small sample of material and say, “I was thinking of that, where could we go with that?” So I’ll send that to her or she’ll send that to me, and then the other person will work it up or adjust it, and start to play with possibilities. Maybe ask the other person, ‘Okay, could you try that as well?’ Very often we get to a state where we have larger passages of fabric and we start to say, ‘How could that drape? How could that move around the body?’ Those are fundamental dimensions. We need to know how it will act in time and how it will perform. Sometimes it will go into large production at that point where we’ll have much more material. We’ll ship it across to Amsterdam or we’ll get something in Toronto, and then Iris will start draping it. If you were to visit my studio you would find hundreds and hundreds of patches pinned up to the wall that we’ve shared.

What does the collaboration with Iris bring you on a more personal level?

The collaboration with Iris on a personal level brings me a sense of surging innovation. But also, a sense that curiosity and wonder is possible.

What kind of vanguard technologies are you looking at next?

I get really excited about working with things that are entropic. Entropy is a very interesting term, meaning trying to be deliberately unstable. And so we’re drawing out very, very thin materials and making them shimmer and tremble and then take on extraordinary amounts of force. I’m also very interested in being able to print chemicals and viscous materials, rather than just 3D printing being about bits of plastic. I’m very interested in working on a continuum of gels and viscous materials so that we can work with things that very gently shift and move into literal living tissues.

Wow, that blew my mind a little bit. What is it like seeing your work in the Royal Ontario Museum?

The Royal Ontario Museum is such an optimistic institution of collecting and orchestrating from all over the world to make this vast encyclopedia. So that’s a very curious sensation, because in some ways, it is an optimism that has passed. Can we possibly build the world by being a colony? By using encyclopedias? Some of that optimism has collapsed in the turbulence of today, but some of it is still very, very real. And it’s a kind of a delicious sense of being with a vast collection here, and making a very real contribution of new work moving forward. The resonance with the layers and layers of history, the archaeology, the beautiful mineral collection, the third largest textile collection in the world, make for a very deep sense of being amongst an absolute fertile gathering of possibility.

The post Architect Philip Beesley on his Friendship with Iris van Herpen appeared first on FASHION Magazine.