Celebrity Kids Are Taking Over the Fashion Industry and We Have Some Questions

If you stepped into a Gap store earlier this year, you might’ve felt a twinge of déjà vu: Its ad campaign featured 16 models showcasing classic garments, solidifying the brand’s reputation as a staple label of the ’90s. The clothes themselves—pleated shorts and oversized denim jackets that Blossom would have worn—were familiar, sure. But there was something about the models themselves. Steven Tyler’s gigantic smile, Demi Moore’s cheekbones and Kim Gordon’s heavy gaze were all there, only on faces decades younger. Who were these people messing around on skateboards and shuffling from side to side while singing an a cappella cover of Color Me Badd’s “All 4 Love”? Were they famous? Should they be?

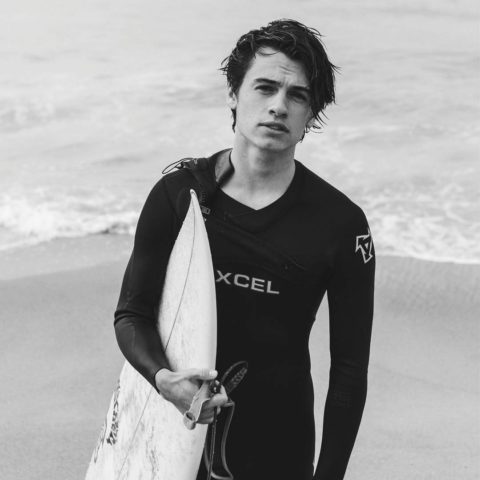

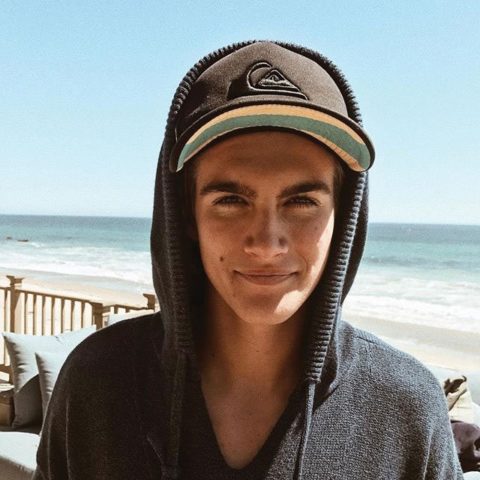

The answer to the first question is easy enough: They were Chelsea Tyler, Rumer Willis and Coco Gordon Moore, examples of the large trend of second-generation celebs appearing seemingly everywhere in fashion culture lately. If that sounds like an exaggeration, try this little test: Pick a ’90s icon at random, see if they have a family and ask Google if their kids have walked a runway, starred in an ad campaign or appeared on a magazine cover lately. (Hello, our cover girl, Hailey!) Madonna? Her daughter Lourdes Leon appeared in a Stella McCartney fragrance launch this past spring. Cindy Crawford? Her daughter, Kaia Gerber, is the face of Daisy Marc Jacobs. Then there’s Pamela Anderson’s son Dylan Jagger Lee, who has been repping for Saint Laurent as of late, and Myles O’Neal (yes, Shaq’s son), who most recently walked for Dolce & Gabbana’s men’s line.

How you answer the last two questions, however, depends on where you’re coming from and probably says a lot about what fame means in the era of “Generation Celebrity Spawn” (so dubbed by The New York Times). If you grew up listening to Aerosmith and Sonic Youth and remember the time Hollywood lost its collective mind when Demi Moore shaved her head for 1997’s G.I. Jane, the stars of that “Generation Gap” ad may seem intriguing because of who their parents are—and possibly because this isn’t the first time the brand has turned to famous progeny to sell its clothes.

In 1989, writer Joan Didion and her daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, appeared in a Gap print ad wearing matching black turtlenecks, and two years later, Diana Ross did the same with daughter Tracee Ellis Ross in classic white tank tops. Those of you born after G.I. Jane, during the time when Moore was most famous for marrying Ashton Kutcher, might instead see young stars who, through constant streams of updates and images, seem more open about the minutiae of their daily lives and are if not necessarily more relatable (let’s not pretend Sofia Richie’s perfectly highlighted Insta isn’t an aspirational follow) at least more reachable. In both cases, Gap likely saw an opportunity to run a concept as old as Hollywood itself through the reliably profitable nostalgia machine.

Over time, the role of celebrity children in pop culture has changed. For decades, if famous family ties weren’t notable for some kind of drama (remember Drew Barrymore’s long estrangement from her parents after a stint in rehab at age 13… or Joan Crawford’s coat hanger scene in Mommie Dearest?), then they were for the obvious attempts made to obscure their existence entirely. Think Emilio Estevez forgoing the Sheen stage name in an attempt to forge a film career on his own merit and Angelina Jolie making her stage name a legal reality in 2002 because, well, she hated her dad. (Of course, a simple name change doesn’t a struggle make; both actors clearly benefited from their parents’ careers and the doors they opened for them.)

Then came the famous-for-their-first-name celebrity babies of the mid-aughts and, with them, an entirely new framework for the “famous family.” When Tom Cruise and Katie Holmes’s daughter, Suri, appeared for the first time on Vanity Fair’s October 2006 cover, sales spiked by 60 per cent. And People magazine reportedly bought the first photos of Angelina Jolie and Brad Pitt’s first child, Shiloh, for $4.1 million that same year and shelled out a whopping $14 million two years later when the twins were born.

These days, clothing and makeup sales seem to be preferred over photos, with celebrity parents looping their young in on the biz. At the beginning of this year, Jay Z and Beyoncé applied to trademark Blue Ivy Carter’s name for a beauty line, and North West modelled the first collection of the childrenswear line that her parents, Kanye West and Kim Kardashian West, launched last spring.

The celebrity children taking over the runways today may be quite a bit older than the A-list-toddler set. At least some of the roots of their popularity come from the same place: the family performance as part of their public persona. While the stories we love to tell ourselves about what “having it all” looks like haven’t changed a whole lot over the years—fame, fortune, a spouse and kids—somewhere between those first family Gap ads of the late ’80s and now, the “and kids” part of that equation became vital in appraising celebrity-ness.

It’s all three of the Willis sisters, in a show of solidarity, going public about their respective sobriety anniversaries in the same week this past July. It’s the Beckham siblings constantly posting selfies with their mom and dad. It’s Cindy Crawford’s son, Presley Gerber, publishing glamorous portraits of his sister, Kaia, as part of a photography project. How can we dismiss the famous as vapid and unworthy of our time and attention if they—like us—have rich, meaningful family lives?

It might sound cynical to label all these public displays of family a performance (even the most skeptical of pop culture nerds would be hard pressed to resist Beyoncé’s documentation of her pregnancy with Sir and Rumi Carter, the announcement of which broke Instagram records), but at least a part of them is. Choices to share information like this with the world aren’t made on a whim, and branding strategists are already co-opting the idea of family values into a type of language that’s more often used to describe royal orders of succession or heritage handbag brands. When the Daily Mail covered Burberry’s recent track record of hiring young celebrity children to front ad campaigns, young stars like Romeo Beckham and Iris Law were described by Karinna Nobbs, digital fashion strategy expert, as having an “authentic pedigree, which differentiates them from models or bloggers.”

Talk like this makes it hard not to see this new crop of young adults building careers in fashion and entertainment as being famous precisely and only because of their parents’ illustrious CVs, no matter how camera-friendly their gaze is or how talented they are. While “having a pedigree” is one pretty ridiculous way to talk about any human being, famous or not, the idea that lineage inherently makes the kids of celebrities better suited to sell clothes is perhaps the most honest acknowledgement of what’s going on here, at least on the part of the agencies and brands booking them.

For the same reasons Hollywood thinks remaking and franchising every blockbuster movie already known to the medium is a great idea (we’re on, what, our 10th Spider-Man film in as many years now?), fashion brands reboot existing genetic property with the belief that an already cultivated audience is likely to want more of the same.

So at what point is there a difference between celebrating the nebulous concept of “family values” and straight-up nepotism? When the eldest Beckham sibling, Brooklyn, was assigned to shoot Burberry’s spring campaign last year, veteran photographers very publicly grumbled at the idea of a relatively inexperienced 16-year-old landing such a plum job.

Then there’s the knotty issue of the homogeneous environments that this focus on ancestry ends up preserving. If the fashion industry has a diversity problem that we’ve only recently started to acknowledge, big labels actively seeking out the children of a generation of celebrities that, let’s be real, present as mostly white isn’t doing much to address the issue.

In an interview about the aforementioned highly lauded Gap ad for classic garments, Rumer Willis told The New York Times: “Regardless of what we do in life, every article starts with ‘Daughter of’… You can fight that or accept and appreciate it.” As spectators, perhaps we can do both. For one thing, fame may beget fame, but it doesn’t always guarantee its permanence. However you feel about Kim Kardashian West’s personality or politics, there’s a reason why Forbes magazine named her a media mogul on its cover last summer. She has developed a talent for making money off sharing details about her life and has put in the work to build that into a multimillion-dollar empire of apps, cosmetics brands, clothing lines and more.

For another, the more banal aspects of the generational fame wave seem to be reaching their logical conclusion sooner rather than later: This is the premise of a new Lifetime reality series—often the last stop on the relevancy train—where the sons and daughters of D-list stars like Steven Seagal and Oscar De La Hoya chase after modelling gigs, complain about their fame-tinged childhoods and drop such profound truth bombs as “It’s not easy being a model, is it?”

And who knows? Perhaps some members of Generation Celebrity Spawn may surprise us by doing more with this revived obsession with heritage than simply being seen and helping to sell designer products. (After all, it’s not as if Hollywood royalty hasn’t brought us great work in the past. Carrie Fisher was once just a celebrity child, though it seems odd to say so.) A year after his inaugural Burberry campaign assignment, Brooklyn Beckham enrolled in a photography program in New York and published an anthology of photographs with Penguin this summer called What I See. The book’s most recurring theme? His family.

The post Celebrity Kids Are Taking Over the Fashion Industry and We Have Some Questions appeared first on FASHION Magazine.