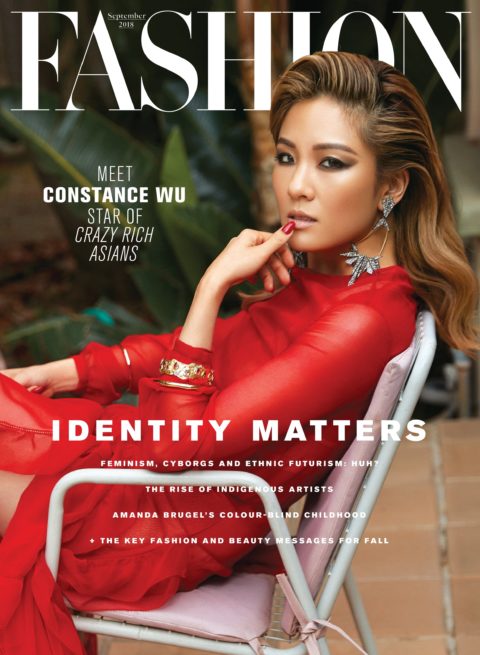

Crazy Rich Asians’ Constance Wu on the Pressure of Representation and Being “the Worst Asian Ever”

I’m waiting to meet Constance Wu outside Blue Bottle Coffee in L.A.’s Echo Park, when I realize I’m not 100 per cent certain I’ll recognize her out of character. I’d seen Wu’s show-stealing breakout work on Fresh Off the Boat, where she plays the mother of food personality Eddie Huang (or some prepubescent version of him) with more nuance than most sitcom moms could imagine, but she likely wasn’t going to turn up looking like Jessica Huang in a loose floral-print dress from the early ’90s.

Not to mention, seeing famous people in real life is a little like hearing your cellphone ringing in the other room—you’re pretty sure it’s your ringtone, but it’s so faint that it could easily be a police siren down the block or your brain messing with you. But then she walks past me and into the café. I know it’s her because (1) I do recognize her, thank you very much, and (2) I get a text from her, letting me know she has arrived.

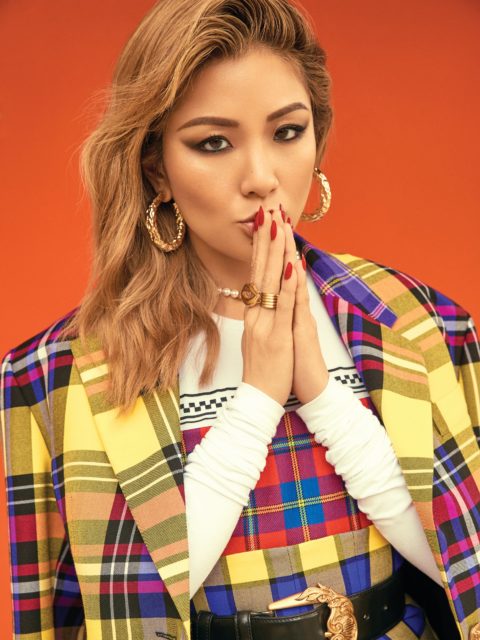

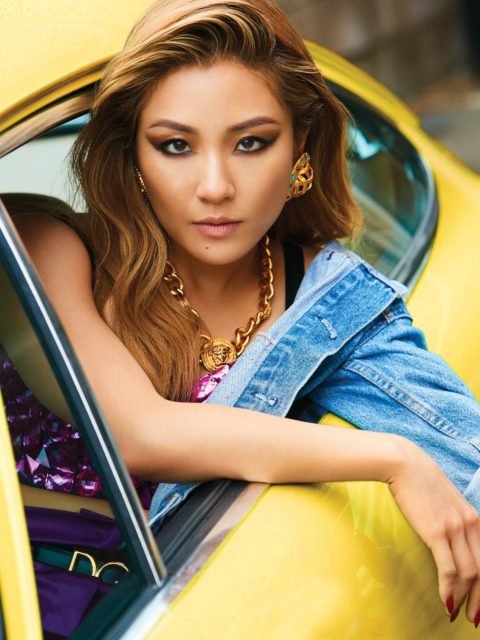

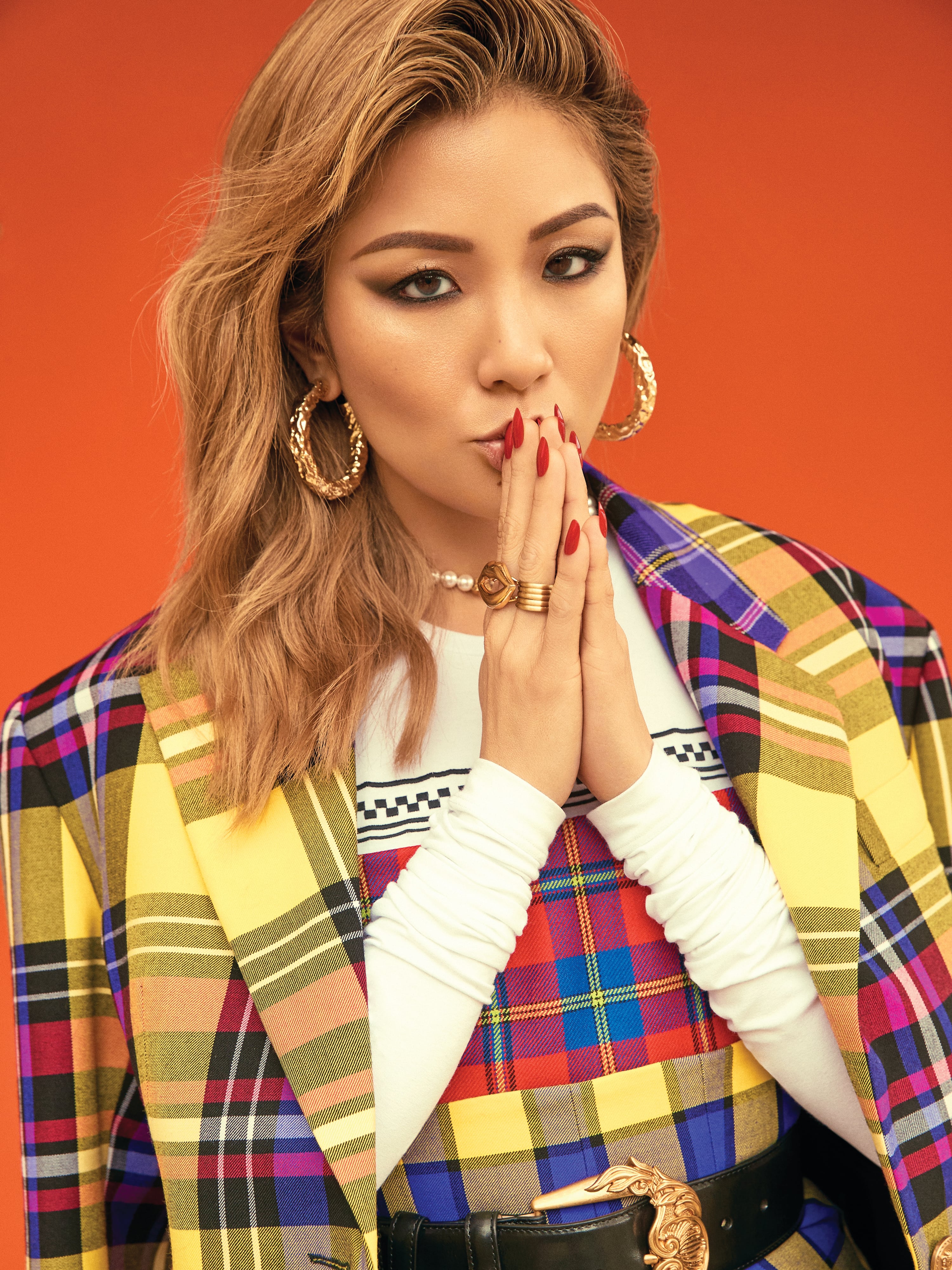

I was right. Wu definitely doesn’t look like she does on Fresh Off the Boat or, for that matter, like her character Rachel Chu from Crazy Rich Asians—the unfortunately groundbreaking late-summer blockbuster based on the bestselling book by Kevin Kwan. Her hair is blond now, though it seems like a stop in a long journey that will inevitably return to black. (It was pink for a while, too.) She’s wearing large reflective sunglasses and a New York Giants ball cap that she adjusts periodically during our interview as a kind of punctuation. The sunnies and cap (the universal uniform of the incognito celebrity) also work perfectly for the neighbourhood—hip but well heeled, approachable despite some rough edges.

I say that Crazy Rich Asians is unfortunately groundbreaking, but actually Fresh Off the Boat is, too. Technically, the ground upon which these projects were built, so to speak, has been broken, but it was broken so long ago that it hardly counts. There hasn’t been a Hollywood feature consisting almost entirely of Asians since The Joy Luck Club in 1993, and the last sitcom entirely centred around an Asian family was All-American Girl with Margaret Cho nearly 25 years ago. It’s not unfortunate that these projects got made, but it’s pretty shameful that they are the only ones.

“I have a pretty good capacity to talk about it in such a way that it’s as clear and insightful as it can be in the moment. I actually think it’s kind of a privilege and an honour—and an obligation.”

Naturally, this is something that Wu is keenly aware of. If you follow her on social media or watch her in interviews or read what she has written in magazines—or what has been written about her (including Lena Dunham’s gushing write-up about her in last year’s 100 Most Influential People issue of Time)—you are no doubt also aware of the startling lack of Asian representation in Hollywood. She isn’t shy about fighting for it, even if her activism has become one of the first things everyone asks her about. “I have a pretty good capacity to talk about it in such a way that it’s as clear and insightful as it can be in the moment,” she says. “I actually think it’s kind of a privilege and an honour—and an obligation.”

But, growing up in Richmond, Va., Wu wasn’t always as conscious. “I don’t think I was ignorant; I just didn’t have cousins or uncles or aunts around me—or anything like that either,” she says. “My parents’ friends were people from the university where my dad taught, and they were all white. I just didn’t notice it.”

And because Richmonders are unfailingly polite, the first time she even thought about her ethnicity, she tells me, was after she had moved to New York. She was picking up bit parts in theatre and indie films and became friends with a girl who seemed to be at all the same auditions as she was. “She was also Asian-American,” recounts Wu. “We went to this party, and after walking in, she said to me, ‘We’re the only Asian people here.’ I hadn’t even realized it. She had grown up in New York, with family around her, so she was used to being in spaces where there were other Asians. I was very used to being in spaces where it was all white people.”

You know, like Hollywood.

Speaking of white people and Hollywood, the café seems mostly occupied by trendy white millennials (some of whom, remember, are in their 30s now) on laptops, presumably writing screenplays or comedy sketches or whatever else Los Angelenos write when they are caffeinated and without Wi-Fi. (The café doesn’t do Wi-Fi.) Wu joins me at my table near the back, where I had left my laptop.

Once Wu is in front of you, you stop noticing much else. And while that sounds like the start of an awestruck profile in a men’s magazine, it has nothing to do with my male gaze. She has a casual magnetism like static electricity. There isn’t anything especially manic, pixie-like or unreal about her. She starts in immediately as if she’s on deadline and only has so much time to impart her thoughts on her art. For her, acting means a lot of homework.

“With every character you go into, you create a life that brought you to where you are, in the present day of the movie,” she tells me. “There are all these clues along the way that you get from the script. It could be something as simple as how much slang you use or if you use curse words or don’t use curse words, if you talk a lot or if you’re very quiet. So you take all those markers from the script and develop who the person is, their interior life. You want your homework to be so deep in your bones that it’s unconscious.”

It’s several minutes into our chat that I start to worry. There’s a difference between interviewing and shooting the breeze. And while the latter is eminently more comfortable for both parties, it can be like when you were a teenager and you talked excitedly on the phone for hours, only to remember the feeling of the conversation more than the content. Of all the difficult behaviours that an interview subject can exhibit, from boorishness to monosyllabism, chattiness is probably the least egregious. Wu isn’t tossing out clichés like a football player at halftime; she’s talking with passion about her passion.

What we’re doing, in fact, is creating a script together. One that, according to her, might give me some clues about her interior life. It actually reminds me of something David Foster Wallace wrote in his essay “Authority and American Usage”: “When I say or write something, there are actually a whole lot of different things I am communicating. The propositional content (i.e., the verbal information I’m trying to convey) is only one part of it. Another part is stuff about me, the communicator. Everyone knows this. It’s a function of the fact that there are so many different well-formed ways to say the same basic thing….”

So, the first clue from Constance the Communicator? She swears a fair bit. “Sorry,” she says. “I say ‘fuck’ a lot.”

A better clue, though, would be why she does all this homework, even for small parts in television shows (not to mention the hours of work she put in with her acting coach for each episode in the first two seasons of Fresh Off the Boat). “I want to honour the human I’m playing,” she says. “If someone were to play me in a movie, I’d want her to really care about what my story was. So I give the same treatment to any character I play.” This is proof of her awareness and sensitivity.

It’s the same empathy that fuels her activism and her understanding that not everyone loves hearing an actress sound off about her acting technique. “If it’s not boring, then it can seem very self-important,” she says. “But I don’t think it’s a bad thing to take pride in your work and to value it. Where the stigma comes in is when people with different values than yours perceive your passions with judgment. But that’s on them. Even though you shouldn’t be ashamed of being a serious actor, you want to be sensitive and not egotistical.”

Speaking of not being egotistical, I should come clean. That thing that Wu said didn’t actually remind me of a David Foster Wallace essay in that moment. In fact, I didn’t read that essay until after I met her, and then it was partially to procrastinate. Mostly, though, I read it because, much to Wu’s Woke Woman of 2018 shame, DFW (who has earned a reputation—not entirely deserved—of being a kind of literary messiah to a certain species of pretentious 20-something white dude who never leaves home without his messenger bag) used to be her hero. It’s a fact that she shares the same way someone might say they used to find Donald Trump attractive.

“I realized ‘Oh, there’s a different way to think about things, in terms of how structures are created.’ I think that’s the first step to becoming woke: understanding that you’re programmed. That you grow up in a system.”

“Not to go back to this—because it’s so embarrassing and he’s a white guy—but the beginning of my thinking of things in a different way was reading David Foster Wallace,” she explains. “The way he breaks down language and education—because that essay is essentially about a dictionary…. I remember that when I read that (I was probably 21), I realized ‘Oh, there’s a different way to think about things, in terms of how structures are created.’ I think that’s the first step to becoming woke: understanding that you’re programmed. That you grow up in a system.”

That understanding is how Wu navigates the inherent challenges of her steady online activism, whether she’s calling out white supremacy, pointing out Asian erasure or railing against Trump’s immigration policy. (“Seeking asylum is not a crime. Taking children from their parents, putting them in tents and cages in a place that’s over 100 degrees heat is inhumane. This is not what America is about. Stand up to #keepfamiliestogether.”) As anyone who has met a comments section on the Internet knows, the potential for setting even supposed allies off is dangerously high. “I don’t like being attacked,” says Wu. “But I like being made aware of stuff that I didn’t think of. And, yeah, sometimes it has a mean edge to it, but the way I think of it is ‘Oh, this person has been hurt before.’ So I feel that.”

Pretty quickly, the character that begins taking shape in this interview-inspired script demonstrates some enviable qualities: She’s understanding and honest, and she has integrity. She’s also willing to say the F-word. Well, sometimes. Peep this tweet from last year, when Wu was sharing her thoughts on Casey Affleck’s impending Oscar win: “I’ve been counseled not to talk about this for career’s sake. F my career then, I’m a woman & human first. That’s what my craft is built on.” That attitude hasn’t changed.

“Of course I want to get more jobs,” she says. “But at what cost? If me speaking my mind about something that I think really matters is going to take a part away from me, then that’s not a part that I want. Those aren’t people I want to work with. Not because they’re not great [Ed. note: There’s that empathy again] but because we have different values and I’m going to feel like shit the whole time I’m on that set.”

Of course, there’s an easier way to get to know the real Wu. Simply explore the wasteland where no one dast venture: the third page of Google results. After we’ve chatted about her activism, her acting philosophy and her family (her parents emigrated from Taiwan, and she has three sisters), I open my laptop to the website Articlebio.com. “This is the best article I was able to find about you,” I say as I pass my computer over to Wu.

“If me speaking my mind about something that I think really matters is going to take a part away from me, then that’s not a part that I want. Those aren’t people I want to work with.”

“Oh, my God,” she laughs while she reads the following: “‘Her style happening is unique with her naturalist performance.… Her trademark is black hair.’ Well, fuck.” She keeps reading, adjusting her cap over the no-longer-trademarked blond hair. “‘In the current time she has no any spouse.’ Can you send me this? It’s fucking amazing. ‘But she is wearing down a partner very soon.’ Because they know this about me.” Her eyes keep scanning the screen.

“‘She is also a good drummer,’” Wu continues.

“Yeah, I wanted to ask you about playing drums,” I say.

“I don’t know where the fuck they got that,” she says. So far, Articlebio is not getting many things right. Which is a pity, because as far as giving details goes, this piece dishes them out like hot takes after an awards show. The article claims she is a good long-distance runner, which is correct, but also says she loves to cook Chinese dishes. “No way,” says Wu. “I can’t even cook. I don’t own a rice cooker. I microwave rice from Trader Joe’s. I’m the worst Asian ever.”

But it gets worse—or maybe better. Her salary, she reads, “‘is a good enough earning, and so is her net worth.’” Then, after the slightest pause, she says: “A thousand dollars is my net worth? Wow. My net worth is fucking a thousand dollars? That’s pretty sad.” Especially since she just bought her first home.

I chime in: “‘She also won the award with the title of best director from the academy awards twice in her life.’ You won best director?”

“Yeah. Not just once. Twice.” Then, after the briefest of pauses—because she understands timing, in both comedy and her career—she adds, dry as a California summer, “And I’m a great drummer.”

You can find Constance Wu on the cover of our September 2018 Identity Matters Issue, on newsstands August 13.

The post <em>Crazy Rich Asians’</em> Constance Wu on the Pressure of Representation and Being “the Worst Asian Ever” appeared first on FASHION Magazine.