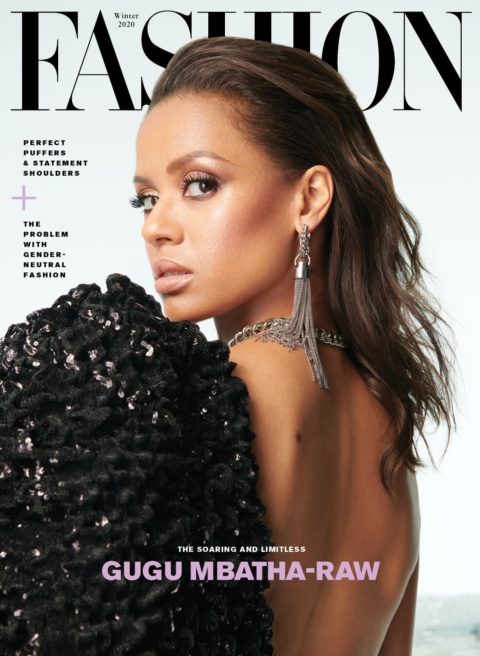

Gugu Mbatha-Raw on Privilege, the Fear of Unemployment & the Ethics of Acting

By the time I arrive at the restaurant on the 44th floor of a downtown-Toronto hotel, Gugu Mbatha-Raw is already waiting at the table, looking like a friend you haven’t seen since high school—familiar and welcoming but not entirely without mystery. She’s dressed casually but professionally—a cardigan may or may not be involved—and her hair is pulled back.

Actually, you know what it is? She looks like a Hollywood casting director’s version of a friend you haven’t seen since high school, which is to say radiant, albeit in a low-key way. Call it Movie Normal.

After introductions, we chat briefly about her latest projects and she starts laughing at my cellphone. But in a nice way. “Do you need me to call Apple for you?” she teases.

See, my phone doesn’t look like a grown-up’s cellphone. It looks like someone took a rock hammer to its upper-right-hand corner, shattering the glass and exposing a mysterious chunk of metal that I pretend is a battery but seems potentially dangerous. Cracks, like crooked sunbeams, cascade down my screen from there, and little dead spots, like burn marks, have recently appeared all over it. My phone doesn’t just look injured; it looks sickly.

“Do I need to sort this out?” she asks.

“What I like about it is that it has a strong point of view and [tackles] the post-#MeToo era in the media landscape.”

She probably could, too. After all, she’s basically an employee of Apple these days. Her latest project—or one of her latest projects, actually—is The Morning Show, an original 10-episode series for the tech giant’s new streaming service, Apple TV+. Starring Reese Witherspoon, Jennifer Aniston and Steve Carell, it takes people inside and behind the scenes of a Good Morning America-type talk show. In it, Mbatha-Raw’s character works as the show’s celebrity wrangler. But with Apple being Apple, she says she can’t explain much more than that.

But the character really is more than she seems. “She has a lot of secrets,” says Mbatha-Raw. “What I like about it is that it has a strong point of view and [tackles] the post-#MeToo era in the media landscape. Plus, it’s America’s sweethearts together in one show. I knew it was going to be amazing and have something to say.”

She can talk a little bit more about Motherless Brooklyn, the Edward Norton passion project about a private detective with Tourette’s syndrome (which can make sneaking around a little tough). It’s a kind of spiritual adaptation of a Jonathan Lethem novel, which is handy for Mbatha-Raw since her character isn’t in the book. “My character comes up as this Woman in Blue that Norton’s detective character is following. She was born in Harlem and grew up in the jazz club owned by her dad. And she works for the community against racial discrimination in housing. She has a law degree. Suddenly she has these layers to her—she’s not just a femme fatale. She has a purpose. She is much more than meets the eye.”

“We never lose the fear that nobody will ever employ us again.”

There seems to be a pattern, or at least a preference, in the characters Mbatha-Raw chooses. They have levels, nuance, complexity—hidden things that will maybe be revealed. Her IMDB page is like the platonic ideal of a working actress: larger and more important roles folded like cake ingredients into a mix of theatre, television and film. “I have been more and more intentional,” she says. “Once you get through the initial [fear of] being able to get a job—and let’s not forget that as actors, we don’t ever take it for granted that we can get work. We never lose the fear that nobody will ever employ us again.”

Then, in 2013, Mbatha-Raw starred as the titular character in Belle, a festival favourite about the mixed-race daughter of Sir John Lindsay, a British naval officer in 18th-century England. This was the year before 12 Years a Slave (rightfully) won the Oscar for Best Picture, so a real-life story about a black heiress from the era when slavery was the status quo was especially significant. “After Belle, I talked to people about the effect it had on them,” she says. “Now, I’m much more conscious of the message of a film and the conversation it can bring up.”

“After ‘Belle,’ I talked to people about the effect it had on them. Now, I’m much more conscious of the message of a film and the conversation it can bring up.”

And the roles haven’t slowed or shrunk since. Her name, while singular in Hollywood, isn’t instantly recognizable in North America. (She’s more known in the U.K., where she’s from, and where Prince Charles appointed her a Member of the Order of the British Empire in 2018.) But it’s getting more and more difficult not to be familiar with her work.

I’m not only talking about inevitable fame, though. Even when she is inhabiting a character with very little connection to the real Gugu Mbatha-Raw, who she is—her core Gugu-ness—shines through. There’s this tiny moment near the end of Irreplaceable You, her Netflix movie from 2018, that gets to what I mean.

In the film, Mbatha-Raw plays a terminally ill woman looking for a new partner for her fiancé before she dies. In one of the final scenes, she is walking with him, playfully balancing on benches. When she reaches the end of a bench, watch her toes as she jumps down: They are perfectly pointed, attached to feet that are beautifully arched. Now, it’s possible that her character has some secret ballet training that we, as audience members, are never told about. But what’s certain is that Mbatha-Raw can’t hide that she knows a thing or two about ballet. In a way, it’s why she became an actor.

“I failed a semi-professional exam, and as this hyper-scheduled, super-high-achieving child, it was a shock to the system. But it was probably the best thing to happen to me.”

“I took ballet very seriously until I was about 15,” she explains. “Then I failed a semi-professional exam, and as this hyper-scheduled, super-high-achieving child, it was a shock to the system. But it was probably the best thing to happen to me. Without sounding immodest, I had never failed at anything. It made me reassess: I wasn’t going to be a ballet dancer. But I remembered my mom as a nurse, doing something she didn’t really have a passion for. I thought: ‘I should do something I love. If it’s not ballet, I’ll do musical theatre.’ And musical theatre led to acting.”

Of course, when you watch her, you don’t just see the pointed toes or her facility for movement. You can feel her discipline, the seriousness with which she takes her craft. You can see the hyper-scheduled, super-high-achieving kid she used to be alongside the woman who still loves homework. “I never had anything land in my lap, but I’m grateful for that,” she says, without implying any kind of chip on her shoulder. “Because it helps you mature as a person. Sometimes there’s an arrested development that happens when you spend most of your time in imaginary worlds.”

“I never had anything land in my lap, but I’m grateful for that because it helps you mature as a person.”

Maybe this is why Mbatha-Raw’s work feels grounded. Through her training, both in dance and, later, at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, she knows her body, like a sniper knows their gun. “Not to sound pretentious, but as an actor, your body is your business,” she says. “You have to invest in it; you have to look after it. Everybody talks about self-care like it’s a new luxury. But as an actor, if you’re not at your best, you’re not going to work. It’s actually a power to use your body and have everything at your disposal.”

When considering an actress like Mbatha-Raw, one can easily fall victim to the halo effect—a type of cognitive bias where, for example, one associates positive personality traits with physical attractiveness. It’s one of the reasons we like our action heroes to look like Chris Hemsworth: Of course he’s a good guy; look how handsome he is!

“Entertainment and storytelling have a hugely valuable capacity for healing.”

Only, with Mbatha-Raw, the presumption of decency feels completely earned. It’s one more thing she can’t hide. She’s not only a talented actress but she might actually be a good person, too: thoughtful, self-aware, giving. The cynic might wonder why a person like that would want to spend time professionally playing pretend.

“It’s so hard, right?” she says. “Because there are so many different types of work that are important. You can literally save people’s lives, like my parents [who both worked in health care]. Or you can make lives worth living. I think that’s another approach when you are an artist: Entertainment and storytelling have a hugely valuable capacity for healing.”

“As an actor, I don’t want to overstate my importance—I’ve gone on two missions, I’m not an expert, I’m an actor—but certainly my role, if it’s anything, is to raise awareness.”

And that could sound pat or obvious coming from an actress—because we all want to think our work is somehow important—but Mbatha-Raw pairs that paradigm with actual work with the UN. “I was just in Uganda earlier this year,” she says. “I think being able to bring a human face to the refugee crisis that often feels unmanageable and go there and talk to people about their families and how they’ve travelled—it’s very valuable.” But, she continues, “as an actor, I don’t want to overstate my importance—I’ve gone on two missions, I’m not an expert, I’m an actor—but certainly my role, if it’s anything, is to raise awareness.”

I haven’t watched Mbatha-Raw’s entire body of work. But she made me cry every time I watched her stuff. Granted, I’m not exactly made out of stone, but her track record is still noteworthy. And it’s all a part of her inability to hide.

What happens is this: Mbatha-Raw appears onscreen, seeming almost out of place—like she’s the only one onscreen with a fresh coat of paint. We keep our eyes on her, and soon we trust her, too. Her humanity is recognizable and a bit addictive. Soon, we are entirely powerless, crying during an episode of Black Mirror.

“You can’t just do it with a selfish intent. I mean you can, but for me, it’s not satisfying.”

She makes you feel. That’s what she can’t hide. She is a vector for feels. It’s her power, but it’s also her purpose. “It’s a challenging job, with all these technical things you can’t complain about because they are still a privilege,” she says. “But with the amount of time it takes to make a film, you have to know that you’re doing something that is really worth it. You can’t just do it with a selfish intent. I mean you can, but for me, it’s not satisfying.”

The post Gugu Mbatha-Raw on Privilege, the Fear of Unemployment & the Ethics of Acting appeared first on FASHION Magazine.