“I Literally Don’t Fit into Chinese Beauty Standards”

During the two years that I lived and worked in Taiwan, I couldn’t find clothes that fit me.

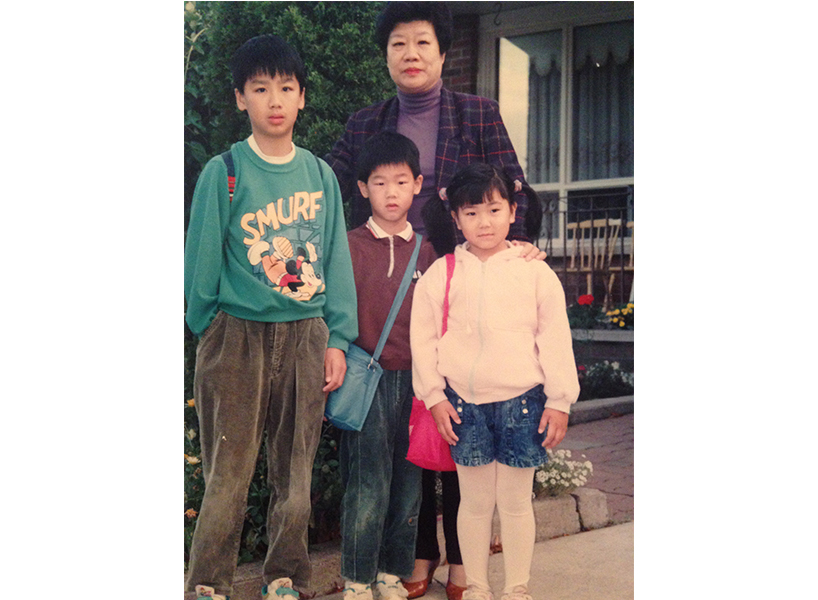

This wasn’t surprising. Growing up, I spent summers in Taiwan, so I already knew that women there are generally expected to be petite. In fact, clothing there sometimes comes in only one size: the rough equivalent to a Canadian size small. I wear a Canadian size 16 in dresses and hover just above five foot seven, so before I moved from Toronto to Taipei in 2014, I made sure to pack my best OOTDs. I even itemized my closet with notes and photos, in case my family had to bring over clothes or shoes for me—which did end up happening.

It wasn’t just the clothes. From a young age, I didn’t fit into Chinese beauty standards and it made me feel shame. I questioned the point of the body positive movement presented in Western culture. On one hand, I prided myself in accepting my appearance, but on the other, I thought about how different my life would be if I were slim. Eventually, I chose to align with the Western idea of embracing your body because there wasn’t a set of rules on how you should look. I immersed myself in various sports as extracurriculars, wanting to prove that my body was just as capable as anyone else’s. It sheltered me from the critique and prejudices so prevalent when I was measured by Chinese beauty standards.

In Taiwan, I saw very few plus-sized women and the ones I did see were often dressed in oversized clothing and had long hair that covered their faces, as if to make their presence smaller in this world. When I wore shorts or dresses, I would hear whispers criticizing the thickness of my thighs. After my first day at a new job, my weight became the subject of a Facebook thread among my Taiwanese coworkers. I was so humiliated by the public ridicule that I pretended it never happened. Despite being born in Taiwan, speaking the language, having dual citizenship and living there, experiences like these made me feel like I never fit what Taiwanese women were *supposed to* look like.

Measuring up to Taiwanese beauty standards

I recently asked my mother what some of the ideal beauty standards were in Taiwan when she was growing up there. She said a small waist, but large hips (for the purpose of childbirth since most women were homemakers). “For more fashionable women, it was a double eyelid and a smile that didn’t reveal teeth,” she said. “A sort of poised and elegant style.” From what I saw on my trips to Taiwan 20 years later, that beauty standard hasn’t changed much. In fact, plastic surgery to achieve the “double eyelid” (where the skin around the eye is reshaped to add a crease) is as commonplace as teenagers getting braces for their teeth. In addition, a survey published in 2011 found that 77% of Taiwanese people expressed a desire to lose weight, which was significantly higher than other Asian markets studied.

In Taiwan, I cringed at the thought of walking past a gym that had salespeople out front because they’d beeline to me, undeterred by my head shake to end the interaction. When browsing department stores, sales associates would bombard me with the latest diet supplements, following me around until I politely thanked them and left the store. I avoided perusing local clothing shops to fend off responses that they didn’t have my size. Living there, I felt like all eyes were on me whenever I entered into a room. Everyone offered unsolicited advice on how to lose weight: Had I tried skinny tea or fasting for a month? Was I willing to try “acupoint catgut embedding,” a form of acupuncture in traditional Chinese medicine where string, made of actual animal intestines, is imbedded into the body via a syringe needle to allegedly stimulate weight loss? I knew these advisers meant well, but these experiences equated weight with my identity, and with each comment, I felt less and less like I fit in with Taiwanese culture—even though I consider Taiwan my home.

Expanding the idea of beauty

In many Asian countries, like Taiwan and South Korea, women inject botox into their calves to make their legs less muscular in appearance (a common cosmetic concern). Viral challenges like seeing how many coins you can rest in the hollow of your collarbone or showing you can fit your waist behind an A4-size piece of paper, also resurface every few years. Asian celebrities, which many young girls see as role models, endorse the idea of being “paper thin” with “chopstick legs” and a “bird’s appetite.”

In Taiwan, I noticed female relatives and friends of mine would only take a few bites at dinner or refuse food all together during gatherings. They would sheepishly say that they’ve eaten a lot that day or were dieting.

“Being thin shows you have time and money to spend on your looks and has therefore become a pursuit of the ‘elite,’” says Sheridan Prasso, the author of The Asian Mystique: Dragon Ladies, Geisha Girls and Our Fantasies of the Exotic Orient. In Asian countries that experienced famine, being plump used to be a sign of a family that is well off enough to have food. “These contrary cultural norms have sprung up to compete with the previous norms, partly as a manifestation of class rebellion.”

Prasso also points to the influence of Japanese anime on East Asia’s beauty standards. Round, childlike eyes, skinny bodies with incongruously large breasts, Prasso says, are anime features adopted into cultural norms. Though the North American body positive movement still has a ways to go in terms of inclusion, conversation and representation is being pushed forward because of the diverse voices getting involved—something that isn’t seen as frequently in East Asia.

“Beauty ideals are changing more frequently than before with the rise of social media, and one could argue to a certain extent the democratization of social media means a greater range of body types are emerging,” says Babette Radclyffe-Thomas, a PhD candidate at London College of Fashion exploring beauty representations. “As people crave authenticity, they will want to identify with people who look like them.” Brands, like Knix and Good American, that sell up to an XXL and size 24, have used social media to cast “regular people” of different shapes, sizes and colour as their models. Yet despite this desire for authenticity, Radclyffe-Thomas says beauty ideals valuing slim, slender, able body shapes still dominate.

According to Prasso, in order for Asian women to join the body positivity movement, there “have to be role models and visual images of women who break through the aesthetic in order to become popular.” Growing up, I only found those types of role models in North American media, so I idealized female athletes like Serena Williams and competitive swimmer Natalie Coughlin. They didn’t look exactly like me, but it felt closer to how I felt compared to the women I was seeing in Asian media.

“Too curvy to be Asian”

When I scroll through social media, I don’t see many plus-sized Asian women represented. Instead, I’m bombarded with images of extremely slim Asian women lined up together holding the latest luxury handbags or posing in front of a mirror with hip bones jutting out of their jeans. I’ve never identified with anything close to those attributes.

Chinese influencer Scarlett Hao, who lived in both China and Germany during her childhood, also received criticism for her body size growing up.

“I think in the beginning it was from the beauty standard side,” Hao says about her mother’s concerns of her weight. “But after, I decided I want to be who I am. I don’t want to lose weight, I’m comfortable with who I am. This is my size, and I’m fine with gaining extra pounds. I think nowadays, she’s more concerned about the health side.”

After Hao arrived in the U.S., she was finally able to find fashionable clothes in her size, which she describes as “life changing.” As a teenager in China, she wore mostly athleisure wear or baggy clothing. She wasn’t introduced to the word “curvy” until her first New York Fashion Week attendance in 2015, where she was snapped by a photographer who said she was “too curvy to be Asian.” In retrospect, the photographer’s comment reflect how the body positive movement still has room to grow in terms of representation, but what Hao remembers is learning a new word to describe her body.

“Because in Chinese, we don’t speak that way. We say people are fat,” Hao says. “So I did all my research. That’s the moment it opened all my doors to this whole plus-size and curvy industry.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/Bw7wUHTBp_V/

Like Hao, whose 192,000 Instagram followers praise her for wearing colour and prints at her size, my wardrobe choices have always revolved around the things I love—ethereal pleated skirts, bold prints and light colours—not the LBD that might make me look 20 pounds skinnier. I’ve never denied myself the experience of trying a trend or hot colour simply because of the unspoken rule that “fashion” is for slim women.

“The clothes definitely always serve people. People never serve clothes,” Hao adds. “There isn’t anything that I couldn’t wear. It’s only clothes I don’t want to wear.”

Perceptions are changing, slowly

If Taiwan moved toward inclusive sizing, not only would young girls grow up more comfortable in their own bodies, but they would also be able to shop off the rack and not have to tediously search for specialty online stores selling plus-size fashionable clothing. While I was there, I could have followed the carefree mantra of “if I forget something, I’ll just buy it there” instead of packing my entire wardrobe.

Even though clothing brands like Air Space and Orange Bear (which I’ve purchased from) are popping up in Taiwan and China offering plus-size options, it’s still a niche market that doesn’t always offer what’s in style compared to regular sizing. And for me personally, seeing more plus-sized Asian women represented in media would normalize body shapes like mine, so that I could feel at ease with how I look in Canada and Taiwan, both places that have shaped my identity.

My mother was a svelte size four at my age, but I have a hard time imagining I’d ever fit my torso into her custom-made qipaos from the ’80s. And now at 31, I’m finally OK with that.

I already fit in, just the way I am.

Related:

I Used to Hide My Shalwar Kameez in Suitcases—and Now I Can Buy Them at Walmart

I Finally Figured Out How to Get a Brass-Free Blonde for My Asian Hair

It’s 2019 and Body Positivity Still Has a Representation Problem

The post “I Literally Don’t Fit into Chinese Beauty Standards” appeared first on FASHION Magazine.