Jean Paul Gaultier Married Kent Monkman to Apologize for Cultural Appropriation. Here’s Why It Matters.

We sit amid a fashion revolution in an industry facing major systemic change. Trend-based talk of hemlines and heel heights is being replaced by more consequential discussions about fashion’s true costs and cultural impacts. We’re stepping outside the confines of certain beauty boxes in favour of healthier ideals and broader representation.

This undercurrent of increased awareness may create the illusion that aesthetically anything goes, but for every line that fashion needed to blur, there’s another yet to embolden: The fashion freedoms of other cultures are not ours for the taking, no matter how inspired or well intentioned we may be. Some things are still sacred. And some things are simply off limits.

Thank goodness we’ve got brave creative souls like Kent Monkman, a Canadian artist of Cree ancestry, whose indelible work helps clarify the difference between cultural appropriation and cultural exchange. By reversing the colonial gaze and challenging pervading notions of history and Indigenous culture, Monkman explores the themes of colonization, sexuality, loss and resilience with exquisite skill, using many media and sometimes counter-appropriating the work of painters like George Catlin and Albert Bierstadt. This tongue-in-cheek turning of the tables has become Monkman’s signature.

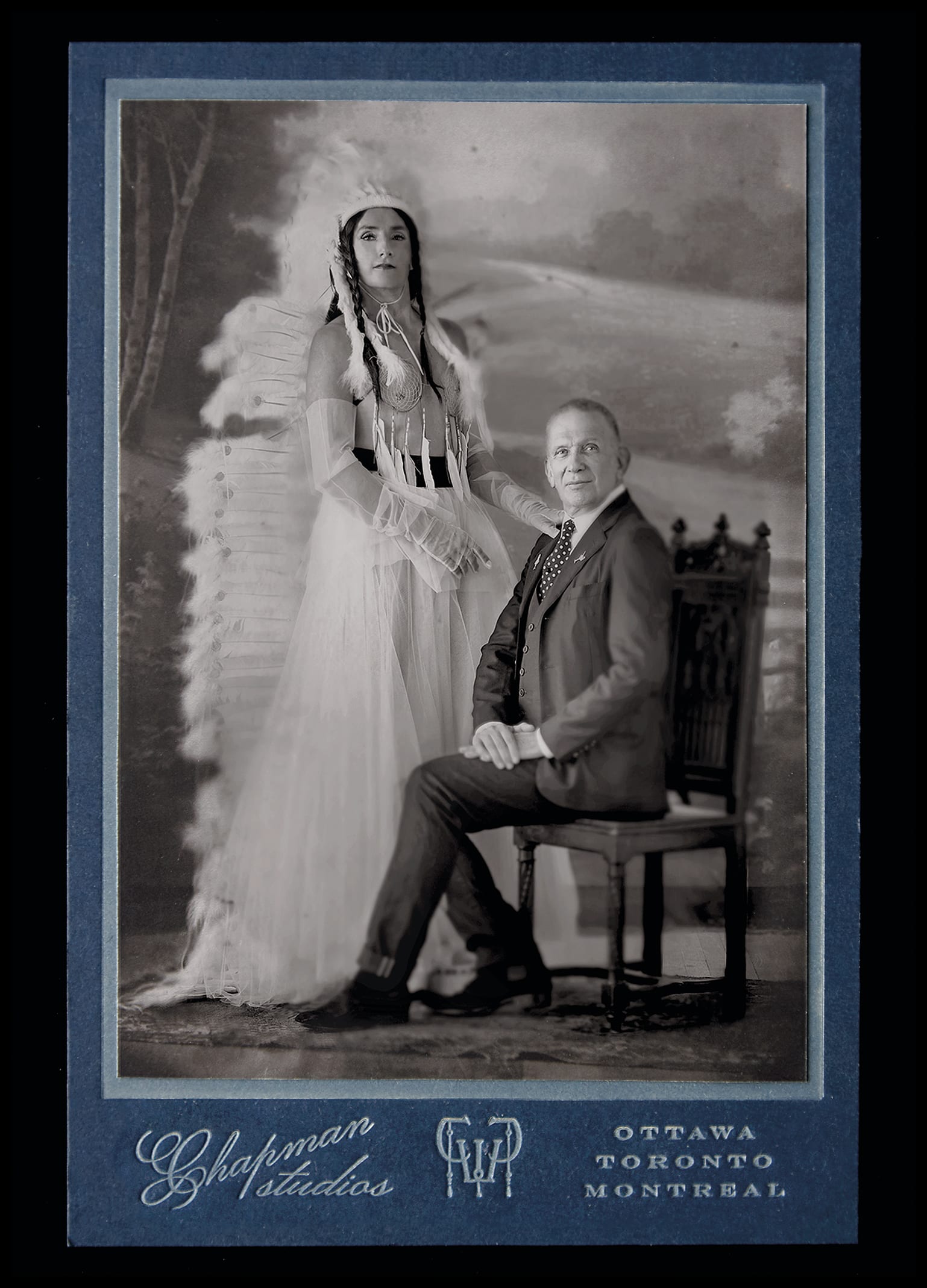

This September marked the first anniversary of Another Feather in Her Bonnet, Monkman’s performance-art wedding extravaganza in which his sensational two-spirit alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, reclaimed a certain white feather headdress by “marrying” fashion’s most legendary iconoclast and champion of the cone-bra corset. Yes, Miss Chief’s betrothed was none other than Jean Paul Gaultier, the man who gave us man skirts and helped blaze the trail of gender expression, famously including Andreja Pejic and Conchita Wurst on his runways. He has been recognized by amfAR for his contributions to the fight against AIDS and received one of France’s highest accolades, the Chevalier à l’Ordre de la Légion d’Honneur.

Dude is definitely doing something right. But on the flip side, Gaultier remains a repeat offender, stealing everyone’s steez, from Hasidic Jews to Boy George. Apples and oranges indeed, but all Diet Prada-fodder affirming that fashion’s enfant terrible was in desperate need of a badass berdache bride to become his better half.

The Montreal Museum of Fine Art (MMFA) played matchmaker to the two provocateurs, having housed the world’s largest collection of Monkman’s paintings as well as Gaultier’s Love Is Love exhibit—a retrospective of his most memorable bridal creations, named in reference to Barack Obama’s statement in support of same-sex marriage and equal rights. But included in the exhibit was Gaultier’s imprudent interpretation of a headdress originated by the Plains People of North America—one cause celebrated at the expense of another’s culture.

“In my conception of clothes…I have always had a mix of cultures, so [the headdress] is an example of that. For me, it was not to make a joke, just as it was not a joke when I did a Hasidic collection.”

In defence of the headdress, Gaultier had this to say: “In my conception of clothes…I have always had a mix of cultures, so [the headdress] is an example of that. For me, it was not to make a joke, just as it was not a joke when I did a Hasidic collection. It is to show the beauty of it. The headdress was traditionally symbolic of power and leadership, and it was traditionally reserved for men, so I thought it would be interesting to suggest that a woman could have more power than a man.”

But to the Plains People, the hallowed headdress, or war bonnet, isn’t simply worn. It is earned, one feather at a time, each gifted in gratitude for honourable deeds over the course of one’s life. To be presented with an eagle feather is a sign of great respect.

The MMFA’s decision to engage Monkman to get engaged to Gaultier “was an afterthought” precipitated by some bad headdress press, says Monkman. The museum’s director general and chief curator, Nathalie Bondil, sent an email to Monkman with the subject line “WHAT WOULD MISS CHIEF DO?” (clearly the best T-shirt slogan since “KALE”), and from there Monkman concocted this most constructive spectacle.

The hallowed headdress, or war bonnet, isn’t simply worn. It is earned, one feather at a time, each gifted in gratitude for honourable deeds over the course of one’s life.

The wedding was a private affair, which may explain why the world managed to sleep through the most significant fashion moment since Michael Jackson’s red leather moto jacket, a portent of fashion’s friendlier future and proof of humour’s ability to heal.

And so on September 8, 2017, the couple were pronounced lifelong “collaborators,” each pledging to “recognize each other’s culture and celebrate their individual uniquenesses as strengths” until death do them part. “Through the alliance of marriage, we learn to understand and forgive the mistakes of our partners and build true understanding,” Monkman said at the time. “And better understanding is really at the core of all my work.”

I asked Monkman whether he felt that the appropriated Plains headdress should have been removed from the Gaultier exhibit—or banned from the beginning—but his response affirmed that it’s time we stop sweeping such insensitivities under the rug. “You can’t police how artists draw influence from the world,” he says, “but you can create awareness about what’s cool and what’s not and how to collaborate and engage each other in a respectful way.” It is possible to “educate and develop sensitivity around cultural appropriation versus mutual exchange.”

Monkman clarifies the power imbalance at the painful root of appropriation. “When you have a dominant culture taking from a marginalized one, that’s where you run into problems,” he says. “Indigenous people have had more than their fashion stolen. They have had land, language, children—every aspect of their life and culture—taken from them. So there’s a lot of sensitivity when things are removed from their original context. People find that traumatizing; it triggers a lot of reactions that relate to these other thefts.”

“You can’t police how artists draw influence from the world, but you can create awareness about what’s cool and what’s not and how to collaborate and engage each other in a respectful way.”

The vows in Another Feather in Her Bonnet acknowledged the rampant appropriation in the worlds of both art and fashion and were perhaps a gentle nod to the groom’s career full of fashion crimes. But Gaultier isn’t the only one. In fact, “there’s a long list of designers who could benefit from a liaison with Miss Chief,” admits Monkman. “Appropriation happens all the time. We’re just paying more attention to it now.”

’Twas only four short years ago that Pharrell’s ELLE UK cover was thought to be stylistically sound when published, only to be slammed by an audience who was #NotSoHappy to see him in a headdress. And almost every year like clockwork, a Victoria’s Secret Angel takes to the stage in appropriated Indigenous attire. The list goes on.

“Indigenous people have had more than their fashion stolen. They have had land, language, children—every aspect of their life and culture—taken from them. So there’s a lot of sensitivity when things are removed from their original context.”

I’d like to think that $h!t like this will soon be extinct. But Monkman is not holding his breath, citing another important factor fuelling the industry’s incessant recycling and ripping off: “The fashion industry is predicated on having to produce an incredible volume of material—new, fresh ideas all the time,” he says. “And in the quest for new ideas, designers often pillage whatever influences enter their sphere without thinking about what they’re doing. Appropriation is easy…stealing something as opposed to reinvigorating one’s own traditions or creating something genuinely original.”

So what are we to do? Monkman suggests that we reach out to the cultures we are interested in and speak to them directly. “Make the dialogue a two-way street,” he says. “Engage a young Indigenous designer. Bring someone up and elevate them with you. If you are going to take, give something back as well.” A great example: Valentino’s Resort 2016 collaboration with renowned Métis artist Christi Belcourt, who worked with designers Maria Grazia Chiuri and Pierpaolo Piccioli to turn her large-scale works into textiles. In an artist statement, Belcourt shared that “the sacred laws of this world are respect and reciprocity. When we stop following them, we as a species are out of balance.”

“Appropriation is easy…stealing something as opposed to reinvigorating one’s own traditions or creating something genuinely original.”

It remains TBD if Gaultier will swap his stripes for sensitivity, but it’s clear that humility is in for Fall 2018—if not forever—and if you ask me, the only real fashion faux pas is an outfit rooted in oppression of any kind.

The post Jean Paul Gaultier Married Kent Monkman to Apologize for Cultural Appropriation. Here’s Why It Matters. appeared first on FASHION Magazine.