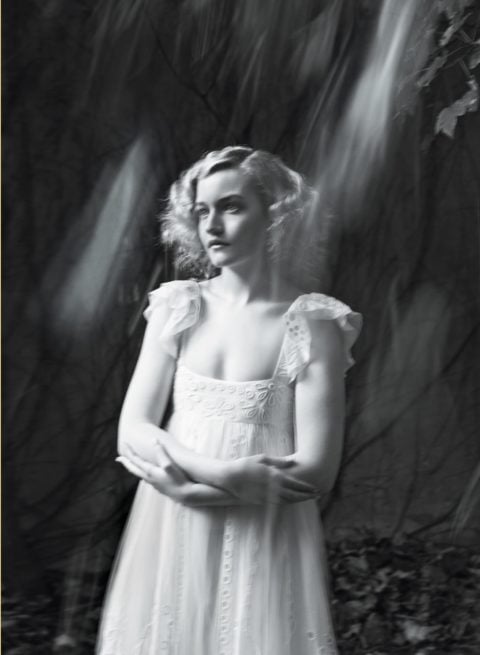

Julia Garner Isn’t Who You Think She Is

Julia Garner is hard to miss—even though the 25-year-old actress is roughly the size of a woodland sprite. (OK, she’s five foot five, which isn’t even that short.) When I get to the diner where we agreed to meet, she’s already there, leaning forward in a booth, wearing a black turtleneck that seems ready to provide cover should she need to disappear. But that would be difficult. Garner the actress—you’ll recognize her if your taste in film and television runs toward the unsettling—can and does disappear into her roles, but Garner the person is unmistakable.

It’s her hair: a controlled eruption of blond curls that would make William Katt—you know, the guy from The Greatest American Hero—swoon with envy. You don’t see curls like hers on television too often—at least not since the days of Chrissy Seaver on Growing Pains or maybe the first season of Felicity. It’s one of the subjects I intend to raise with her: how curls are often cut, straightened, covered up or otherwise discriminated against in showbiz and how they might make someone a hero.

There’s probably a metaphor in there, too.

She brightens when I approach, and we immediately fall into an easy conversation. She’s open and friendly, despite the unconscious motions of millennial discomfort: pulling at her collar and then running her hands through her hair, gathering it up and moving it from one side to the other, like a kid who doesn’t want to eat her potatoes. Before I can ask about that hair—or anything else for that matter—we’re interrupted by one of the diners on his way out. He’s sporting a buzz cut and a bright green shirt he likely got at the “Why Yes, I Am an Embarrassing Dad Store.”

“Is that Ruth we got here?” he says, not acknowledging my presence. “We just finished Ozark, and I thought it was you!” Garner is just as gracious with him as she was with me when I said hello. The man compliments her work and then heads out before anything becomes uncomfortable. A few moments later, he’s back with a camera. “My wife is going to love this,” he beams.

It was almost as if the whole interaction were a bit of theatre orchestrated for my benefit, to show not only Garner’s reach but also her low-key grace despite her growing fame. It wasn’t, of course. But since I had wondered whether Garner, who has been acting for nearly a decade but mostly in indies, has started getting recognized, it was a bit uncanny.

And, fine, asking whether an actress gets recognized is about as groundbreaking as asking who she’s wearing on a red carpet. But it seemed like an especially appropriate question for Garner. Because her biggest role at the moment—at least until Dirty John, a true-crime series, based on a popular podcast, that came out late last year—is as Ruth, the whip-smart, shit-talking quasi-outlaw/sidekick to Jason Bateman’s Marty on Netflix’s Ozark.

“When did that start happening?” I ask.

“It actually first started in Brooklyn,” replies Garner. “Because I was in indies, that seemed to be where I was recognized most often.”

And now look: That girl from Martha Marcy May Marlene—and a surprising number of other cult-based works, like Electrick Children, where she played a Mormon teen who believes she was impregnated by rock music, or Waco, where she was one of David Koresh’s Branch Davidian wives—is all grown up and getting spotted in Manhattan. If you can make it there….

Garner isn’t anything like the characters she plays. She doesn’t sound like them, and she doesn’t act like them. Granted, this is true of most actors (though, ha ha, certainly not all). But, like in the biblical “Parable of the Sower,” she plants the seeds of her characters in fertile ground: They grow out of who she is. Take Ruth in Ozark, for example. Garner has managed to create a character that’s intimidating, resourceful and strong while keeping this thread of vulnerability humming just under the surface. “The vulnerability is the easy part,” she tells me. “Ruth’s strength—that was the challenge.”

“The vulnerability is the easy part. Ruth’s strength—that was the challenge.”

Plus, she already had that thick, rusted Missouri accent from an earlier role in Tomato Red. She figured she’d impress the producers with it in her audition for Ruth. “Casting offices in New York are tiny,” she tells me. “So while I’m waiting, I can hear all these other auditions for the same part. And none of them are trying out the accent.” She decided she’d forget the accent, too. Only, she couldn’t. “I had prepared so much with the accent that I couldn’t even remember my lines when I tried to do it with my normal voice.” Obviously, breaking out her Missouri twang worked out for her—spoiler alert: she got the part—but the fact that she almost caved to peer pressure of her own making is telling.

You get the sense that, like a lot of people who were painfully shy as kids, Garner has what my family used to call the Appropriateness Gene. It’s a potent blend of sensitivity, empathy and self-awareness that makes, for instance, watching cringe-comedy nearly impossible unless there are ample pillows nearby to hide under. Basically, the Appropriateness Gene—which has yet to be identified by geneticists—makes you want to do what’s right/expected, and it causes you pain when others don’t. “My mom used to get me to eat vegetables by making me feel guilty,” explains Garner. “Like, ‘You don’t want these carrots to fail in their life’s purpose, do you?’”

“My mom used to get me to eat vegetables by making me feel guilty. Like, ‘You don’t want these carrots to fail in their life’s purpose, do you?’”

Famous people will often talk about how awkward, nerdy or generally uncool they were growing up. This is either an attempt to seem relatable or proof that everyone goes through periods where they feel as if they don’t fit in. It usually feels disingenuous—except when Garner says it, you believe her. “I was one of those kids whose parents were actually worried about them. Like, ‘She’s such a sweet girl,’” she says, pretending to be her parent, “‘but is she going to be OK?’”

Acting was actually what brought her out of her shell, though she still identifies as a bit of a nerd, even now. She looks down and her voice drops, as if she’s about to confess something that will be painful for both of us: “I really like Vanderpump Rules.” When that doesn’t convince me of her current nerd bona fides, she tells me she knits, too. The shame.

“I was one of those kids whose parents were actually worried about them. Like, ‘She’s such a sweet girl, but is she going to be OK?’”

She lowers her voice often, actually, apologizing in advance for saying something horrible—like how parents maybe shouldn’t force their children to perform before they are ready—that never turns out to be horrible at all. She can’t help it. It’s a function of her Appropriateness Gene.

But that (entirely fictional) gene might also be the key to outsized talent. After all, has there ever been a shy, sensitive child who isn’t also a keen observer and preternatural listener? Even now, that’s what Garner notices when she watches other people perform: if, and how well, they listen. “I can always tell; that’s the most important thing,” she says. “It’s about figuring out what a character wants. It sounds horrible, maybe, but people only wake up in the morning because they want something from the day. If you listen, you know what that is. And then you react to that.”

The harder you listen, the more present you can be. “If I can remember what I did in a scene, I will ask to do it over. Because it means I wasn’t in the moment,” she says. That’s the other side of the shy/sensitive/self-aware coin: an inherent perfectionism that is both inspiring and exhausting. “If I’m not in pain—if something isn’t hurting—at the end of the day, I worry that I haven’t worked hard enough,” she says. “I just want to know that I’ve done everything I can.”

“If I’m not in pain—if something isn’t hurting—at the end of the day, I worry that I haven’t worked hard enough.”

But that all-or-nothing, go-for-broke commitment begins before the official work even starts: These days, Garner doesn’t even go in for an audition unless she knows she’ll be crushed if she doesn’t get the part.

There’s something refreshing about that passion, something dangerous. But it’s also the perfect response to an industry that has a habit of breaking people down and flattening them. Of taking their curls and straightening them. “I know I’ll never be cast as, like, the popular girl because there will always be someone prettier,” she says. “And I can’t play a typical daughter because I don’t look like anyone. I want to take advantage of being the New Thing, because I’ve learned that there will always be a new New Thing.” And so why not only go up for roles that interest you—that only you can bring to life?

“I want to take advantage of being the New Thing, because I’ve learned that there will always be a new New Thing.”

And maybe that will change as Garner’s career progresses. Even some of the best actors in history have accepted roles and done work they clearly weren’t passionate about. Hell, whole careers have been built on a performer’s need to pay a mortgage(s). But in a perfect world, wouldn’t everyone have Garner’s level of passion? Wouldn’t everyone be willing to work until they hurt and listen until they were lost in the moment? A perfect world doesn’t necessarily mean an easy one. Perfect can be messy, even if you don’t see it that often, especially on television.

The post Julia Garner Isn’t Who You Think She Is appeared first on FASHION Magazine.