The Avant-Garde Approach: Rei Kawakubo Tackles Business Like Her Designs

When the Internet company I was working for in the mid-’90s switched me from World Cup soccer coverage to fashion, I found there were two things about my new beat that flummoxed me: the zealous reverence for Italian Vogue and the repeated mention of someone named Ray.

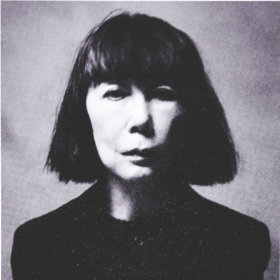

“Ray who?” I was dying to ask. His name sans surname was always coming up at the fashion events I attended. It was not until some time later that I figured out “Ray” was Rei Kawakubo. And by the time the Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York finishes in early September, the greater public will also be on a first-name basis with the 74-year-old Japanese designer.

In talking about Kawakubo’s Comme des Garçons, one inevitably mentions certain landmark events in its history: its atomic-chic Destroy collection in Paris in 1982; its bulbous lumps-and-bumps Spring 1997 collection; the triple-sleeved shirts; the perfume that smells like photocopier fluid; the braces ad; the chromatic progression from fetishized black to red to gold.

Less known are certain fillips of information that have slipped through the media sieve in amusingly terse interviews meted out to journalists over the years. Like the fact that Kawakubo’s mother was an English teacher and a divorcee—the latter a rare and renegade thing to be in postwar Japan. Some attribute Kawakubo’s sustained rebellion against fashion norms to the original matriarchal revolt. She hasn’t commented on that—at least publicly—but her quotes in the show notes from the exhibit provide some insight into her unorthodox point of view: In 2011, she said, “I never give myself any boundaries or let them interfere with my work.” In 2012, Kawakubo made her manifesto clear: “Personally, I don’t care about function at all…. When I hear ‘Where could you wear that?’ or ‘It’s not very wearable’ or ‘Who would wear that?’ to me it’s just a sign that someone missed the point.”

And what is that point? It’s not about making clothes for Kawakubo; it’s about creating objects for the body that have a conceptual and transgressive connection to the human silhouette. Or, as she said in 2015: “Things that have never been seen before have a tendency to be somewhat abstract, but making art is not my intention at all. All my effort is oriented toward giving form to clothes that have never been seen before.”

On display at the museum are all the highlights of Kawakubo’s profoundly punk career, if we take “punk” in the larger sense of uncivil disobedience. There is the Comme des Garçons “lace”—the falling-apart knits of the early ’80s. There are the signature asymmetry, wigs and frayed hems and the outsized ruffles, bows and tulles. What will be more difficult to exhibit is design of a less tangible kind—which is to say, the Comme des Garçons way of doing business.

Kawakubo has said that she “‘design[s]’ the company, not just clothes.” The privately held company generates somewhere in the ballpark of $220 million a year in revenue. It does so with business ideas that are as avant-garde as the clothing.

Unlike other typically hierarchical corporations, Comme des Garçons has a horizontal strategy that carpet bombs the market with diffusion lines, spinoff brands, collaborations and unusual retail concepts. Besides the main women’s and men’s collections, there are currently 18 different product lines, ranging from Play, Tricot and Shirt to Wallets, Girl and Homme Plus. Then there are the numerous collaborations, which Comme des Garçons began doing before other brands. There were the prescient retail projects, like the guerrilla pop-up marts, which it stopped in 2011 when everyone else caught on. There are also the market-shopping experiences, like Dover Street Market.

But perhaps the most unusual way Kawakubo has designed her company is that it has evolved a stable of designers. Neither a collaboration, nor a collective nor a conglomerate, the umbrella organization of Comme des Garçons and its satellite of designers grow out of a modern-day master-apprentice guild: Junya Watanabe, Tao Kurihara (though she discontinued her line in 2011), Fumito Ganryu (who left the company earlier this year) and Kei Ninomiya.

And then there is Gosha Rubchinskiy. Comme des Garçons owns the Gosha label, but it is unclear whether the Russian designer has the same relationship to the mother ship as his Japanese counterparts. In the case of Watanabe and Ninomiya, each designer is independent yet conversant with Comme des

Garçons vernacular and, as such, benefits from the protection offered by the company’s big tent. The Gosha venture, whose post-Soviet aesthetic is entirely distinct, is an outlier and, possibly, a new kind of business in the Comme des Garçons universe.

Comme des Garçons benefits from the pervasive buzz of all these lateral associations without the full weight, presumably, of having to run them. It operates a little like a franchise that somehow escapes the blanket sameness of, say, Tommy Hilfiger. The Comme des Garçons business model has its rules but retains the playfulness and wiggle room essential to its cool factor. This makes its design every bit as radical as a three-armed shirt, and somehow, despite that, it’s a money-maker.

The post The Avant-Garde Approach: Rei Kawakubo Tackles Business Like Her Designs appeared first on FASHION Magazine.