The Man Behind Phantom Thread’s Spectacular Costumes

Mark Bridges is a costume designer extraordinaire. He got his start working on the cult adult comedy Dream On in the early ’90s, and has been in a fruitful partnership with director Paul Thomas Anderson for the last twenty years. Bridges’ costume credits include everything from dressing a groovy 1970s porn star in Boogie Nights, to the hardscrabble oil prospectors in 2007’s There Will Be Blood. In 2012, he took home an Academy Award for his work on the vintage Hollywood-inspired silent film The Artist.

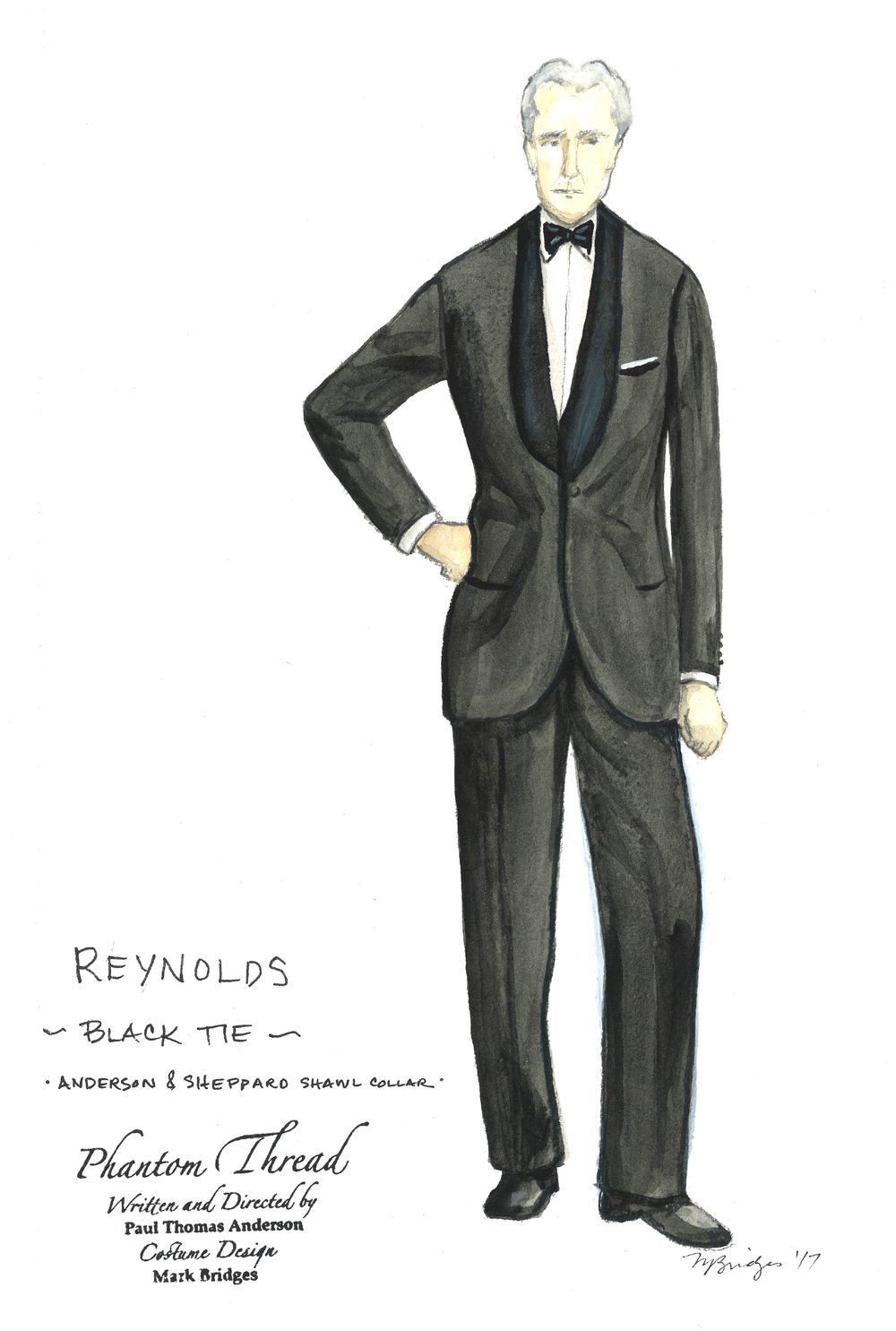

Bridges’ latest venture is Phantom Thread, a deep dive into the sumptuous atelier of fictional fashion designer Reynolds Woodcock, and a film whose tagline may as well be “gowns, gowns, beautiful gowns.” Woodcock, played Daniel Day-Lewis is a tortured, obsessive designer whose draining relationship with his muse Alma, played by Vicky Krieps, veers unexpectedly off course. It’s a movie filled with stiff organza, antique lace and tailoring so sharp it makes the eyes prickle.

FASHION spoke with Bridges about finding inspiration in Cristobal Balenciaga, the antiquated couture techniques he discovered, and designing costumes for the most anticipated fashion movie of the year.

What was your first thought when you heard you would be costuming a film set in 1950s high society Britain?

I didn’t believe my good fortune, that the next thing I do would be with a director I’ve been working with for 20 years would be such a dream job. And then I began to think about how we would create what was needed to be such sumptuous garments for the story to be believable.

Phantom Thread has been embraced by the fashion industry as a “fashion movie.” Did you feel extra pressure knowing that for many people, the costumes would be the biggest draw to go see the movie?

No, that never crossed my mind really because my goal as a costume designer is just to figure out how best to tell the story through clothes. And if things capture the imagination of the public, that’s fantastic. I really don’t think about those kind of distractions when I am planning to design for film. I am more about character and the story.

The character of Reynolds Woodcock is much modeled on Cristobal Balenciaga. In terms of costume design, which elements of Balenciaga’s work did you draw from and which did you leave behind?

I think the idea that the vendeuses (editor’s note: an old-fashioned word for saleswomen) in his salon were dressed in a particular way is what we used from Balenciaga. We also looked at the kind of work smock he wore, but ultimately we made a different shape for Reynolds Woodcock. Paul [Thomas Anderson, the director] drew for the script, the idea that Balenciaga did his own cutting and draping when creating a garment the way Reynolds Woodcock does (which is something Dior did not do). As far as designers, I think Reynolds Woodcock and Cristobal Balenciaga are two very different designers. One was groundbreaking and one was perhaps just a man of his time; Very different in their respective levels of creativity.

In the film, the dresses almost come to life onscreen and at some points in the film, are almost treated like sentient beings. How did you manage to make these dresses feel like living objects?

I just feel like I’ve made the dresses appropriate to the time and place and character and perhaps that’s why they feel alive. They have a luminous quality to them. They’re labored over in the story as something very precious, I think rightfully so. The audience feels that kind of magic. If there is a technique, it would be choosing particularly photogenic fabrics that have some life to them whether it would be satins or taffetas that have a shimmer and photograph well. That’s why they jump off the screen.

Many of the dresses in the film are rather unusual – for example, the dress for the Countess with the arched collar and the slits in the bodice is rather reminiscent of Henry VIII, and the bridal dress has what I can only call a “boob shelf.” Can you elaborate on your decision to include these rather unusual design elements in the film?

The slashing detail on Henrietta’s dress was actually a suggestion that Daniel made when we were designing what was going to be Henrietta’s first gown, a sort of emblematic dress of the House of Woodcock. He did a very rudimentary stick figure sketch of the dress and talked about slashing with some kind of pearls and the slashing. And so he went back to his work in front of the camera and my cutter and I figured out how the little sketch can be realized into a full-fledged working garment. That was very fun.

The boob shelf design was a compilation of something we’ve seen in a Reynolds’ gown before, the black lace Chantilly dress that she wears earlier in the film. So we carried over that sleeve and collard treatment. The little band underneath was from a vintage dress that we had that I liked. But it was not atypical at that time to have something that felt a little demure and also a little sexy. There are offshoots of that dress made later by Dior and similar to a dress Princess Margaret wore. So the “boob shelf” idea, was kind of typical at that time to heighten a certain aspect of the figure.

In the film you used real couture techniques to create the dresses. Out of all the techniques, which one felt the most archaic?

Well, I think the amount of handwork that was typical of couture at the time was perhaps most archaic. When you look at Dior’s salon in the ‘40s and early ‘50s, there were only about two sewing machines. The rest of the sewing was done by hand. So the enormous amount of hand sewing and finishing at all the raw edges of the seams inside, everything was done by hand. As well as the required foundation garment that was put on to reshape the body to a certain silhouette before the gown was put on. I think those two things needed to be historically accurate and something today we wouldn’t even think of.

Did Reynolds Woodcock himself (Daniel Day-Lewis) have a hand at all in designing any of the costumes?

Actually, I would often ask Daniel to choose a color for either Alma’s wedding suit or the dress with the antique lace trim. I would just hand him the swatch book and ask him to choose a color. So yes, I do think he had a part in the design, as well as his contribution towards the Henrietta dress. He chose those colors as well. I think it was important to him to have a sense of authorship with the gowns as the character who is supposed to have created them.

Phantom Thread opens in Canadian theatres January 5th.

The post The Man Behind <em>Phantom Thread</em>’s Spectacular Costumes appeared first on FASHION Magazine.