The Problem with Quarantine Merchandise

We’re now *deep* into quarantine, which means you’ve probably perfected your WFH outfit. And with most people spending much more time inside due to COVID-19, it’s inevitable that there’d be a shift in what we wear (because honestly, who wants to wear jeans inside?). Maybe your WFH fit consists of a cozy-yet-chic sweatsuit. Perhaps it’s a tie dye top paired with the softest leggings you own. It possibly even includes a T-shirt with the slogan “Quarantine and Chill” emblazoned across it. If so, how do you feel about that? Cool? Helpful? Conflicted? A little bit icky? All of the above?

After the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, the temporary shuttering of many retail business around the world and an increased need for products like face masks and hand sanitizer prompted fashion and beauty businesses to adapt, with many brands pivoting in order to produce essential items. Designers like Christian Siriano, Louis Vuitton and Tommy Hilfiger all halted production on their lines, instead putting their resources towards sewing face masks for frontline workers in need, manufacturing hand sanitizer for hospitals and donating T-shirts to nurses and doctors who need to change multiple times per day. But among these efforts for businesses to adapt during COVID-19, a new revenue stream has emerged: quarantine merchandise.

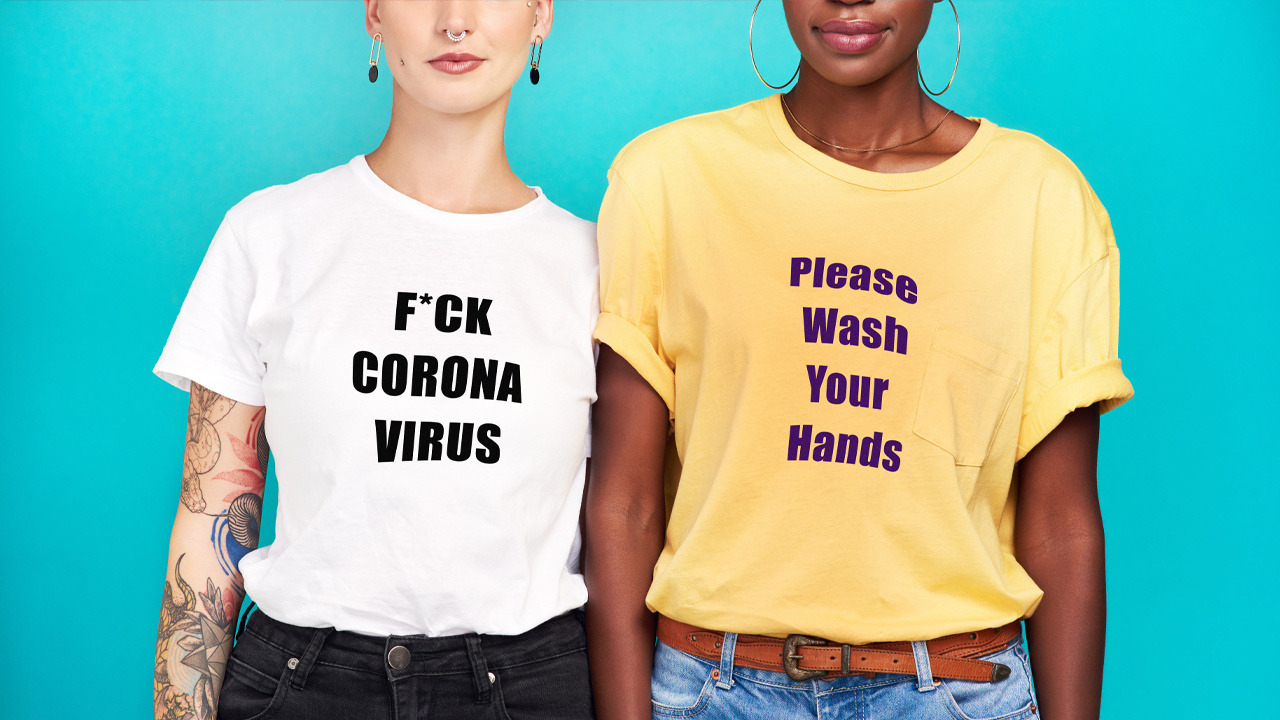

Existing brands like Scott Disick’s “Talentless” have turned out hoodies and tees with catchy messages like “Please Wash Your Hands,” stationery companies have begun producing quarantine notepads (no doubt meant to document this strange time in our lives), several Canadian fashion brands collaborated to sell a limited supply of shirts featuring the faces of popular female health officials, and new brands with a pretty niche angle have emerged entirely. Established after the onset of COVID-19, The Virus Collective is one such label. Run and designed by “a collective of fashion industry professionals” who are “choosing to work anonymously so that the brand’s focus remains on its mission and not on the egos or names of those involved,” a spokesperson for the company told FLARE via email, the brand produces T-shirts, hats and sweatshirts with coronavirus-related slogans like “Dab When You Cough” and “F*ck Coronavirus” on them. They donate 25% of each purchase to the World Health Organization’s COVID-19 Response Fund.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B90eMF5BAZM/

And while, in theory, donating money towards COVID-19 relief in *any* way is great, and, as someone coming of age in the early 2000s, I’m a sucker for a good graphic tee, something just feels kind of off about using COVID-19 as a selling point. It turns out, I’m not alone in feeling this way.

Many brands are changing their messaging to reflect COVID-19

Mary Young, the CEO and designer of her namesake intimates brand, is familiar with companies trying to capitalize off the social cause of the moment and has noticed an uptick in the way quarantine is advertised to consumers. ”I have seen a few different companies advertising their products as ‘the best quarantine outfits,'” she says, which is probably something consumers are familiar with by now.

Scrolling through Instagram, it’s inevitable that you’ll zip past an ad for COVID merch or re-branded copy on already existing brands (for example: popular online brand ASOS has re-jigged their product copy to reflect the current state of the world, with sections hawking “Virtual Party Hits” and “Mood-lifting florals).” “I can understand that,” Young says of companies trying to sell their existing products—like sweatpants—by fitting them into the time we’re in. “We’re all at home and aren’t wearing jeans every single day.” But, despite that fact, Young doesn’t feel that brands should be telling customers specifically what to wear or buy during quarantine, “because there are bigger stresses right now and what to wear should not be one of them.”

But quarantine merchandise feels a little insensitive

In addition to these advertising shifts, Young has noticed the proliferation of COVID merch—and she’s not that into it. “I’ve definitely seen brands launching new products with new designs that are COVID-19-focused or quarantine-focused and that sometimes even have that copy on a T-shirt,” she says. “In my opinion, if you want to be raising money for frontline workers or different organizations, you don’t have to create a new product that has the name of the pandemic on it.”

The creation of an entirely new product that draws inspiration from quarantine is unnecessary for myriad reasons, paramount among them being the fact that COVID-19 has been so devastating for those suffering from it. Considering the families of those who have tragically died from it and, of course, frontline workers who are risking their lives every day, wearing merchandise with slogans about the virus feels kind of insensitive. Because, in the words of Kourtney Kardashian to her sister Kim, “People are dying.”

Which, to be fair, is something that many brands are aware of—and trying to be sympathetic towards in their marketing. “Everyone on the planet, including the team behind Virus Collective, is impacted by this pandemic so of course there is a continued dedication to and vigilance in approaching the topic and the designs with a sense of respect and empathy for what’s happening,” a spokesperson for Virus Collective told FLARE. “Still, fashion is a form of self-expression and the brand has been able to genuinely tap into the emotions and experiences that a lot of people are experiencing on a daily basis in an authentic way and raise money for World Health Organization’s COVID-19 Response Fund in the process.”

But some people disagree. While it’s undeniably helpful to raise funds for a charitable organization, Young thinks there’s a line when it comes to what businesses are doing. “Are you doing something to catch on to a trending hashtag? And if you’re putting ‘Quarantine and Chill’ or ‘Quarantine 2020’ on a sweater or whatever it may be, you’re really trying to jump onto something that’s happening.”

While the fashion world is no doubt driven by trends, Young says that there’s a difference when it comes to capitalizing on quarantine merch—not to mention an insensitivity. Sitting at home with our cheeky quarantine apparel makes light of a serious situation, and the fact that people are putting their health at risk every day on the frontlines while many of us are at home. “I have friends that are nurses and doctors and what they’re seeing, what they’re sacrificing, is much bigger than a ‘Quarantine and Chill’ hoodie,” Young says.

Coronavirus merchandise is also wasteful AF

For Dr. Anika Kozlowski, an assistant professor of fashion design, ethics and sustainability at Ryerson University, brands that are using COVID-19 are doing one thing: “They’re just capitalizing on a trend,” she says. “They’re capitalizing on a crisis and it’s shameful.”

Not to mention bad for the environment. While the idea of rocking a COVID-related tee while at home may sound cheeky, what are the chances that people will *actually* keep this as part of their regular wardrobe once this is over? Unlike that fun trip to Disneyland when you were eight, will we really want to even be commemorating this challenging, scary period of time with memorabilia? Kozlowski, the only person in Canada with a PhD in sustainable fashion, is guessing that the answer is no, which means a greater likelihood that these products are just going to end up in landfills or oceans before you know it. (ICYMI, only 25% of clothes collected or donated to thrift shops are actually sold in store, meaning that a large majority of the clothing that we donate ends up in landfills or abroad, shipped to re-processing plants, used as rags or sold to secondhand retailers in countries like Kenya).

“I don’t think that we should be producing single-use products—and I consider these to be single-use T-shirts,” Kozlowski says. “You’re buying it to fund a charity, but what happens to that T-shirt after? How many times are you going to wear a ‘Quarantine and Chill’ T-shirt?” she asks. “And when you’re done with it and you donate it and it goes into a charity shop or ends up in a developing country, who’s buying that T-shirt? Who wants that?”

In fact, the professor is quite certain this will be the case and cites the recent example of the January 2020 wildfires in Australia as proof. Alongside calls to donate directly towards credible charities battling the fires, merchandise popped up. ”[This pandemic] is not the first time we’ve seen this,” Kozlowski says. “Anytime there’s some sort of a crisis [there’s this merchandise and marketing].” If you want to have a discussion about the effect of this merchandise, Kozlowski recommends asking what happened to all those Australian wildfire shirts.

Kozlowski knows *exactly* where they are: off the coast of Ghana. Kozlowski recalls doing an interview with Vogue Business in January on the ethics and sustainability of “moral merchandise” (merchandise with a social message behind it). ” I was working in Ghana and talking with [on the phone with an editor from Vogue], and I’m staring at the exact type of T-shirts in landfills and on the coast of Ghana where all of secondhand clothing ends up,” she says.

Quarantine apparel speaks to the impulse to commoditize everything—even a global pandemic

While we definitely don’t need more merchandise polluting our planet, we shouldn’t be too surprised that people looking for ways to show their support during the pandemic are doing so through their purchases. Numerous studies have found that millennial consumers are more engaged and willing to purchase from brands that support a cause, with a 2017 College Explorer study from Alloy Media finding that 95% of college-aged students in the Unites States are less likely to ignore an ad that promotes a brand’s partnership with a cause. Other surveys found that almost 90% of consumers say that, given similar price and quality, they’re likely to switch to a brand associated with a good cause from a brand that isn’t. This is research that companies are obviously aware of—and capitalize on—through cause marketing, the cooperative effort between a for-profit and a non-profit for their mutual benefit.

And while there isn’t a lot of definitive research to support it, it’s not difficult to think that there must be something to the idea that consumers are more willing to donate towards a cause if they receive something physical in return. Which isn’t an experience entirely unique to COVID-19 merchandise.

“That’s normal with any time you donate to a charity, right?,” Kozlowski notes, using the example of stickers that say “I donated.” “Maybe it’s just a larger symptom of the type of society we live in where we always need some sort of reinforcement for our actions.”

Young would agree—and hopes it’s a symptom that we can eventually move past. “It’s just another Instagram-able moment,” she says. “And I really do hope that as we continue to grow as a society, we move away from buying things for the sake of posting on Instagram.”

In short: just donate

All of this is not to say that those who are selling pandemic merchandise are ill-intentioned or just looking for a profit. The aforementioned Virus Collective has pledged to donate 25% of each purchase to the WHO indefinitely. But the fact remains that producing pandemic products—and the costs that come along with that—restrict many companies from donating more to organizations aimed benefiting COVID-19. A 2011 study by Aradna Krishna, a marketing professor at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business, found that people gave less money in direct donations to charities when they made cause marketing purchases.

“Of course the brand would love to donate 100% of the proceeds,” a PR representative for the brand told FLARE, ”but Virus Collective is a business and has expenses. While other brands are shutting down or having to lay off employees, we’ve found a way to work with distributors and bring work safely to individuals in the US and EU. We’re incredibly proud of what we’re accomplishing as a business and as a fundraiser.” [In a follow-up email, Virus Collective said that since they launched, the company has been able to “stay in the green and has not operated at a loss thus far;” stressing that the brand was never intended to be a highly profitable venture or a means to profit off of a difficult time].

Not to mention the fact that, unless a company is breaking down their costs for you, consumers can never be entirely sure where the rest of their money is going. From an ethical perspective, Kozlowski finds it problematic because brands that donate a portion of their sales to charity are given a tax receipt. “Usually there’s not a disclosure around what percentage of it is going where [aside from the charitable piece],” Kozlowski says. “[Brands] say: ‘1% of all sales [goes to an organization].’ Where is the rest of that going? What does that really mean? There’s not a lot of transparency about how that money is used afterwards.” And, she asks, “how much funding are the brands themselves getting back in terms of tax receipts?”

“It seems like so many brands are jumping onto this bandwagon [that] it must be beneficial for them,” Kozlowski adds.

It’s because of this that many people, Kozlowski included, feel the best course of action isn’t to buy another T-shirt, but for people to donate directly to organizations themselves (and this includes organizations or fundraisers aimed at helping people—like factory workers—who may be out of work due to the pandemic). “Just make a specific donation yourself,” she advises. “I don’t think it requires you to have to purchase to support a cause.”

And this applies to celebrities, too. Over the past two months, we’ve seen celebrities both hawk their own merchandise for the cause (like singer Selena Gomez, who announced on March 26 that a percentage of each purchase from her newly launched “Dance Again” line would go towards MusiCares’ COVID-19 Relief Fund), and create entirely new companies (like Mila Kunis and Ashton Kutcher, who created a quarantine-themed wine with 100% of proceeds going towards relief efforts) in order to donate varying percentages of the proceeds to various COVID charities.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B_K2aI2nNWR/

Which, is a nice sentiment, except for the fact that a large majority of these A-list celebs are asking normal people, many of whom may be facing job and financial insecurity, to make purchases when they could simply donate the money themselves. That’s pretty infuriating. ”When I saw celebrities raising money through T-shirt sales, it just made me so angry because you’re a celebrity who has multimillions and you’re asking ordinary citizens in a time of crisis to donate money for this charity,” Kozlowski says. While it’s great for celebs like Gomez and the Kunis-Kutchers to spread awareness about organizations and throw their support to fans through exposure, “If you feel so strongly about it, you donate your own money,” she says. (It’s important to note that since her announcement, Gomez *has* donated directly to the Plus1 COVID-19 Relief Fund.)

“There are so many other ways to help out that are significantly more important than buying a T-shirt,” Kozlowski continues. “If you’re buying that T-shirt so that there is money going to a specific charity, you’re better off donating that entire amount directly to that charity as opposed to it being filtered through a brand.” That way, you support the cause directly and don’t end up with another T-shirt to eventually donate.

And if you want to shop, support local businesses

If you are looking to support brands during the pandemic, purchase something that you’ll actually wear and use—something preferably made and sold locally as well. Young says that although her brand saw an initial downturn in sales in February, right before the COVID-19 crisis really hit, they’re currently on par with where they were sales-wise at the same time last year. And even if people aren’t able to support with their dollars, Young says the bigger conversation around supporting small businesses during this time has been noticeable. “I’ve seen that really affect how people are even engaging with our brand online and email; even just people posting in stories and sharing their own thoughts on different brands to be supporting,” she says. “It has been really heartwarming to see the community that we’ve built make sure that they’re supporting the brands that they love.”

Young wants her customers to know her brand is still here, doing everything within their power to ensure everything is sanitized and cleaned and employees are as safe as possible, and still committed to helping people feel good about themselves—especially now.

“We’re really just trying to build our community around what’s going on,” she says. “During these times when you’re dealing with a lot of anxiety and stress, self-love often falls to the wayside. A lot of people are talking about, ‘There’s more times to do face masks and different things like that.’ But in reality, that doesn’t always help with the anxiety that we’re going through during a normal workday…we want to create a digital space to help people feel less alone during these times.”

Whether that translates into people buying Mary Young products or not, that’s still amazing. “If not, then at least they have a place online where they feel that they’re part of something.”

The post The Problem with Quarantine Merchandise appeared first on FASHION Magazine.