Why we love flankers: A tribute to these fleeting fragrant sideshows

See this season’s top flankers »

When I was 14, a friend and her family picked me up to go to a play. When I got into the car, her normally reticent 18-year-old (and thus super-intriguing) brother said to me: “Wow, you smell amazing.” I had recently received my first bottle of Issey Miyake’s L’Eau d’Issey as a birthday request—I liked the idea of a watery smell and felt a Japanese designer was terribly sophisticated—and was taken with spraying it into the air above my head and twirling under the mist.

This encounter cemented my decades-long love for the ’90s classic (and for being told I smell great), during which time I collected many of the variations of it that came and went on the local department store counter like colourful siblings in town for a short visit. On a given day, I’d pick a version to match my mood: Summer of 2005 or 2008 if it was warm outside, A Drop of Cloud (2009) if I was feeling pensive, Fleur de Bois (2010) to cultivate a much-needed air of mystery. Somewhere along the way, I actually stopped wearing the original, since each new one offered what I loved about it along with a new and exciting twist.

I didn’t realize until later that my dresser’s pleasing arrangement of glass pyramids was made up of what fragrance companies call “flankers,” a relatively recent phenomenon designed to bring attention back to best-sellers and capture new audiences. A flanker is usually a limited-edition remix of an existing scent based on a season, an ingredient, a time of day or an age group (“sport” or “fresh” versions are usually designed to reach a younger crowd). “When we launch a flanker, the sale of the original goes up,” says Steve Mormoris, senior vice-president of global marketing, American fragrances for Coty Prestige. Occasionally, though, a flanker will outshine its ancestor: Giorgio Armani’s Acqua di Giò is an oft-cited example.

It’s a lot cheaper and easier to launch a flanker than a new scent—not so much because of the juice itself as what it comes in. A perfume bottle can take two years and hundreds of thousands of dollars to design and produce; tweaking an existing one’s colours and accoutrements takes about half that time. The other big-budget saving is in the marketing: Customers are already aware of the brand, so the house merely needs to remind people of what they already know.

“Flankers accelerated the conception of perfume being a commodity versus a work of art or a luxury product,” says Fabrice Penot, who co-founded the niche perfume house Le Labo after becoming disillusioned with his job as a marketing executive for a big fragrance house (he took care of Acqua di Giò for many years). But he points out that not all flankers are created equal. “Some brands, like Chanel for example, very rarely do a flanker. They change the shape of the bottle, like Coco Mademoiselle, and the fragrance is amazing because it took years to develop. It’s not just light, or summer—it’s actually a beautiful territory that they are digging into. They are adding a layer.”

From a perfumer’s perspective, the challenge is artistic, not commercial (though it’s typically a smaller job with a smaller payday than a new fragrance). They need to change the scent enough that it feels new, but not so much that lovers of the original won’t recognize it. “When you make a new interpretation, you need to surprise the applicant,” says Alberto Morillas. The creator of the newest L’Eau d’Issey, Lotus ($116, at department stores), a composition of aquatic lotus blossom grounded by white musk, Morillas also made two of the original watery floral fragrance’s flankers and is already at work on next year’s. He talks about being careful to maintain the style of the original, while leaving his signature—a Mediterranean freshness born of his Spanish roots. “Every time, it’s a very different formula,” he says. “But this is the magic of interpretation—it’s the same story, but different.”

Morillas, the creator of successful flankers like the oft-referenced Acqua di Giò and four versions of Flower by Kenzo, believes the secret is approaching each new brief with enthusiasm. “If you think, ‘Oh, my goodness, again? A new flanker—these are boring,’ it will be really boring. But when you start with a lot of passion for the new flanker, you put your best into it.”

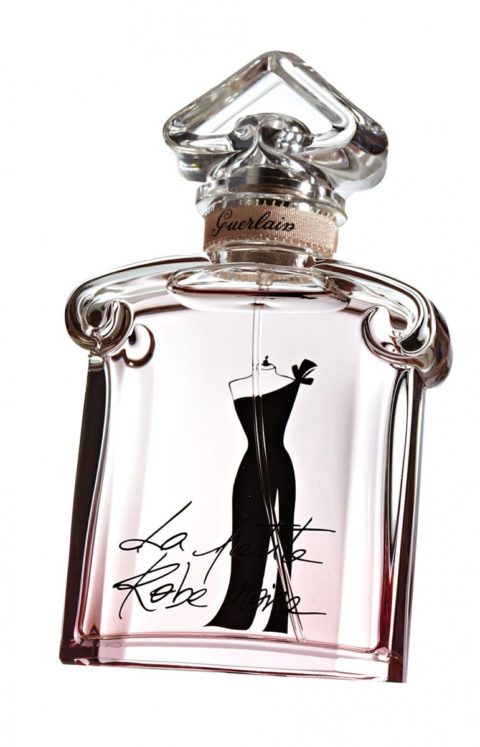

Given the choice, Sylvaine Delacourt, director of perfume creation for Guerlain, prefers to create a new formula from scratch with complete freedom rather than revisit an existing one. With one exception: A few years ago, she was asked to reinterpret Guerlain’s classic L’Heure Bleue, created by Jacques Guerlain in 1912, which is her own signature fragrance. While she finds it beautiful, a common criticism is that the powdery floral is too strong and unapproachable, perhaps a little old-fashioned. Although Delacourt had access to the original formula, written out like a cake recipe, she chose not to look at it or to mathematically rearrange the components, as some perfumers would, instead improvising based on her knowledge of the scent. “L’Heure de Nuit is like the daughter of L’Heure Bleue,” she says of the updated version she formulated with Guerlain’s in-house perfumer, Thierry Wasser. “She has a beautiful smile, she has beautiful curves, she has beautiful memory, but with ingredients of today like orange blossom and jasmine. At the time, there was more iris.” So does she wear her own new and improved version? “No, because L’Heure Bleue is my perfume. This is my signature.”

While some flankers are undoubtedly marketing ploys with little artistic integrity—changing the colour of a bottle cap does not a new fragrance make—there may also be a soupçon of snobbery involved in their dismissal. True connoisseurs pride themselves on judging a scent without looking at the name or the marketing campaign, but a summer version of a big hit is unlikely to see pride of place on their dressing table, however lovely. It’s in this sheepish spirit that I confess my flanker habit to Penot and ask if there is any hope for me. He laughs. “There is hope, because you’re talking about one of the most amazing creations of the last 20 years,” he says, to my relief. “When Issey Miyake does a flanker, it’s very thought-out. They are focusing on one ingredient, but you can tell that it’s just another book of the main story, and you can tell that this book is going to be fascinating as well—it’s the same writer, it’s the same adventure when you read it. So you don’t need your soul to be saved.”

For me, the story is tinged with pathos, since I’ll never be able to restock my precious stash of Summer 2008. “Next year, there will be more flankers, and people are a little bit sad about this,” says Morillas. “I enjoy creating a new flanker—something that when people smell it, they think, ‘This is so good, I can’t understand why I won’t be able to smell it next year.’”

The post Why we love flankers: A tribute to these fleeting fragrant sideshows appeared first on FASHION Magazine.